Solutions for the biggest conservation challenges plaguing the Chesapeake Bay actually start at the farthest reaches of the watershed—on out-of-state farms and in Capitol Hill offices

The Chesapeake Bay watershed is one of the most impressive in the world. It covers 64,000 square miles across six states and the District of Columbia. It is home to about 18 million people and 2,700 species of plants and animals—more than any other watershed in North America. Prized sportfish like striped bass (locals know them as rockfish) swim and spawn here, and waterfowl hunters from all over visit for the annual Canada goose migration.

It is truly one of a kind, and D.C. residents are lucky to have the Bay right here in our backyard.

But this watershed also faces some serious challenges. By the mid-20th century it was clear that a few hundred years of intensive urban, agricultural, and industrial development had left the waters toxic and hypoxic, or lacking oxygen. Fish, wildlife, and anyone living or recreating in the watershed had been affected by the negative impacts of pollution.

To help track and improve the health of the watershed, the University of Maryland’s Center for Environmental Science releases an annual Chesapeake Bay Report Card which scores the Bay on its water quality, fisheries health, and other vital signs. The first report card in 1998 gave the Bay a failing grade of 27 out of 100, but the results just released in May scored it at 54 out of 100—a strong uptick, but also showing there’s still a long way to go.

With clean-up efforts showing steady progress right where D.C. policy makers can see it, the Chesapeake Bay watershed could become a true conservation success story and model for the country. Over the next three weeks, we’ll be highlighting some of the major conservation issues remaining for Bay fisheries, some possible solutions, and what this means to sportsmen and women across the region.

Let’s start with what Pennsylvania farmers have to do with Chesapeake Bay rockfish.

A Committed Coalition

With a watershed extending across so many state borders, and with so many species, businesses, and American pastimes at stake, in 1983 an impressive coalition came together to take action. The governors of Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania joined the mayor of D.C., the Chair of the Chesapeake Bay Commission, and the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency—operating on behalf of all federal agencies—to sign the first Chesapeake Bay Agreement, an unprecedented commitment to watershed-wide cooperative action to restore the health of the Bay.

But even after three decades, there is much left to be done. So in 2014, the six original partners recommitted to a new Chesapeake Watershed Agreement, and brought the remaining Bay states—New York, West Virginia, and Delaware—into the fold. This new agreement will provide a framework for achieving watershed restoration in the next ten years and beyond.

A Watershed-Wide Responsibility

When thinking about how to clean up the Chesapeake Bay, it’s important to note that the Bay’s waters don’t generally empty out into the Atlantic Ocean. More than 180,000 miles of rivers, streams, and creeks starting as far away as Cooperstown, N.Y. ultimately deposit their waters in the nation’s largest estuary, mingling with tidal waters from the Atlantic. Most of what goes in stays in, so thousands of miles of upstream impacts are concentrated in one downstream basin.

This means that the state of the Bay really depends on what happens in and near the tributaries leading to it. For instance, nutrient pollution from urban development and agricultural lands upstream have negative impacts on rockfish in the estuary, which are sensitive to low oxygen conditions created by toxic algal blooms. (You can read more about what nutrient pollution means for sportsmen right here.)

Farmers are the Keystone of the Bay’s Restoration Efforts

This is why the 2014 Chesapeake Watershed Agreement focuses on reducing the excess amounts of nitrogen, phosphorous, and sediment loads in the Bay, mostly by helping farmers upstream to keep nutrients on their fields and out of our public waterways.

There is no place more important to this effort than Pennsylvania.

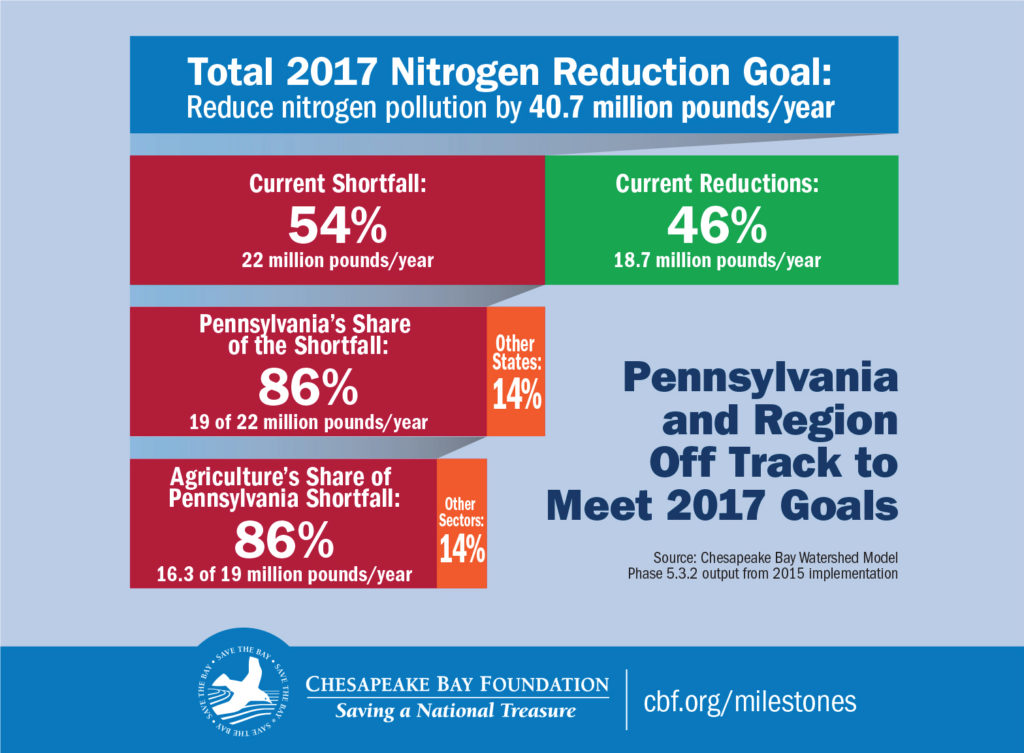

For instance, the total goal is to reduce nitrogen pollution in the Bay by 40.7 million pounds per year. According to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF), stakeholders have so far only been able to achieve 18.7 million pounds of reductions per year, watershed-wide. But if Pennsylvania were to achieve 100 percent of its state goals, most of which could be addressed through better farming practices, the state could knock out another 19 million of the remaining 21.3 million pounds per year, or 86 percent of the overall Bay’s nutrient reduction shortfall.

To dial it in even further, most of that shortfall could be addressed by tackling farm runoff in just five counties in south-central Pennsylvania.

Enter the Farm Bill

Chesapeake Bay stakeholders have a plan. If Pennsylvania can help its farmers to fully implement a handful of farmland conservation practices, the state could achieve most of the nutrient reduction goals for the entire Bay system. Farmers would get assistance in restoring forested areas alongside streams, strategically converting cropland to grasslands and wetlands, storing manure more safely, and building fencing to keep livestock out of streams.

The problem, as usual, is a lack of local funding to make it happen. Fortunately, the federal Farm Bill is intended to support exactly these types of initiatives.

For instance, the Regional Conservation Partnership Program has a funding stream dedicated to innovative, collaborative, landscape-scale solutions to nutrient reduction challenges in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. And the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which helps farmers, ranchers, and foresters to conserve environmentally sensitive land, is being deployed across the region to help farmers turn unproductive cropland into pollution-reducing stream buffers. CRP’s enhancement program is especially effective at contributing to clean water and better fish habitat in the region.

The Farm Bill’s Future

These critical programs are set to be reauthorized by Congress in 2018. They’re not perfect, and they don’t work everywhere, but we’ll be fighting to renew and improve them for places like the Chesapeake region. Because without $5 billion in annual Farm Bill conservation funding, we have little hope of solving the Pennsylvania problem, and there are similar situations all around the country.

You can help TRCP fight for Bay restoration funding. Tell Congress that you support Farm Bill programs that reduce nutrient pollution, benefit farmers, provide habitat for fish and wildlife, and help to guarantee all Americans quality places to hunt and fish by signing the petition at CRPworks.org.

And of course stay tuned for the rest of our series on efforts to clean up the Chesapeake Bay and rebuild its fisheries, from the bottom of the food chain on up.

must save The Bay

We keep cracking down on the farmer who can barely survive. Many farms closing and becoming delopements. Here is your problem. Home owners .drive ways, roads, etc. To many chemicals and run off that far exceed what the farmer of the land ever did.