Tree Planting in Annapolis, Md.

Do you have any thoughts on this post?

This holiday season, we’re toasting to the success of our partners who are working together to build a better future for sagebrush habitat and #350species

With a quick glance across the West, it’s clear why cooperation is a cornerstone of conservation. This is the region where multi-generational ranching families move cattle, sportsmen and women pursue trophy elk and cutthroat trout, energy and timber companies extract resources, and outdoor enthusiasts climb peaks, bike single tracks, and explore some of our nation’s largest networks of public lands.

This rich diversity of demands on the land increases the pressure to conserve sagebrush habitat and the 350 species that depend on it. In recent years, an unprecedented effort to conserve the sagebrush ecosystem—which is home to iconic species like greater sage grouse, mule deer, and pronghorn antelope—brought together conservationists, ranchers, energy developers, federal and state agencies, local governments, and outdoor recreation businesses in a landmark victory for effective collaboration.

But because administrative action to not list a species doesn’t remove trees, plant sage, and improve habitat in and of itself, a policy win for sage grouse is only half the battle. It’s our partners who are at the forefront of on-the-ground conservation work, ensuring that habitat remains intact, energy development and grazing practices are done wisely, and sage grouse ultimately remain free of the threat of an Endangered Species Act listing for years to come.

As folks come together with friends and relatives this holiday season, we’re thinking about our family—the network of fine conservation groups that unite over wildlife, habitat, and our hunting and fishing traditions—and how working together is better than working alone, especially in sagebrush country. Here’s some of what they have accomplished.

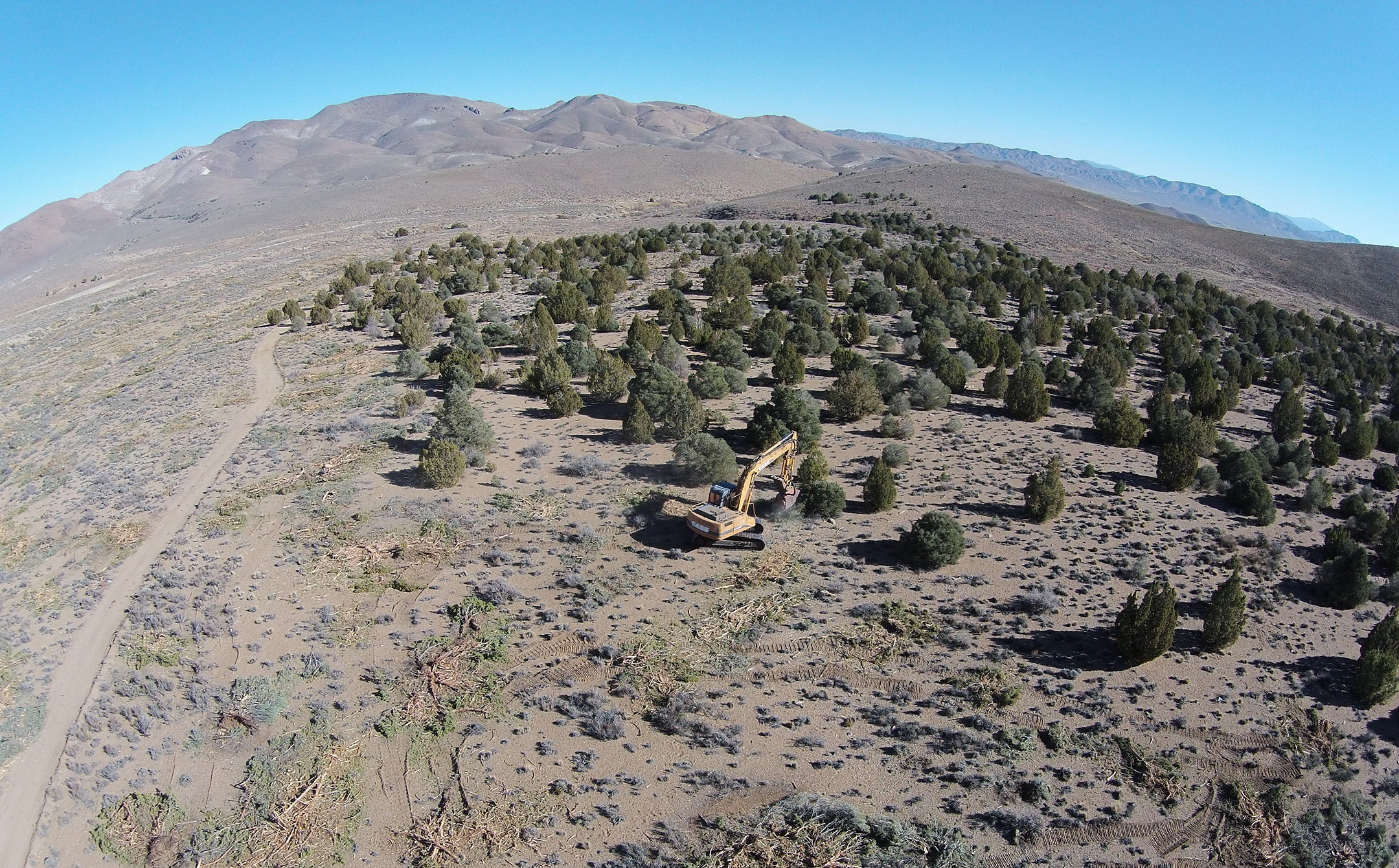

In sage grouse country, Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever have embarked on a mission to improve sagebrush habitat by treating areas of encroaching Utah juniper. This thirsty tree has invaded the sagebrush landscape and built up heavily wooded areas that can’t support sage-dependent species. Working with the Sage Grouse Initiative, PF has helped treat approximately 14,000 public acres, with another 12,000 scheduled for treatment over the next two years. That’s in addition to ongoing treatments underway on other state and private lands adjacent to the project.

The scale of the project is huge, especially considering all the organizations that must work together to gather the necessary land access, scientific expertise, and manpower, including local offices of the Bureau of Land Management, Natural Resources Conservation Service, and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, plus state wildlife agencies, conservation districts, local working groups, permit holders, and private landowners.

It’s a testament to how much can be accomplished by working together. Partnerships have enabled more on-the-ground success than any one individual group could have accomplished on its own, and this has allowed improvement of sage grouse habitat across fence lines, regardless of ownership.

Improving conditions for one species creates benefits for many others (one of the reasons conservationists are so obsessed with quality habitat), and that’s where the Mule Deer Foundation comes in. Muleys and sage grouse have the same habitat needs in many areas, especially on winter ranges, so responsible management of grazing and conservation of critical wintering areas benefits both species.

Throughout their range, mule deer populations are stagnant or declining, largely due to loss and fragmentation of habitat. In order to improve and restore mule deer habitat at an unprecedented level, MDF is working across sage grouse country in close coordination with (you guessed it!) partners. A 2014 study actually demonstrated that measures taken to conserve sage grouse in Wyoming also benefit mule deer migration routes, and it highlighted the role of state and federal agencies and NGOs working together.

Among agencies, tools like targeted easements on private lands and limitations of disturbance on federal lands can proactively conserve remaining migration corridors, stopover habitat, and winter ranges for mule deer. Included in those protective measures is the state of Wyoming’s sage grouse “core area” policy, which limits development in the state’s key grouse habitat, as well as conservation easements and agreements with private landowners to limit development.

To complement MDF’s existing habitat restoration program, the Natural Resource Conservation Service and the Sage Grouse Initiative have come on board to enable greater private landowner cooperation. With a substantial portion of mule deer winter range occurring on private land throughout the West, this partnership has enabled more conservation success than MDF could have achieved on its own.

The Wildlife Management Institute has lent their leadership and science expertise to the sage grouse conservation effort through the annual WMI North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference. In our circles, we refer to this conference as simply “the North American,” and the fact that it is so widely recognized is a testament to how many people WMI has reached.

For several years now, the North American has included sessions on sage grouse to highlight and expand upon efforts by WMI, state fish and wildlife agencies, and partners to advance conservation. Together, we have an opportunity to address some of the toughest issues affecting sage grouse country, and getting together in the same room helps us to forge important connections and trade ideas.

The Nature Conservancy has been working to protect sage grouse by improving and expanding current conservation efforts across the sage-steppe ecosystem, not only for the iconic bird, but also to protect families and communities in the West. Along with partners like the U.S. Department of Agriculture, they’re innovating new techniques for sagebrush seeding and planting in priority landscapes, and collaborating with private landowners to drive forward on-the-ground action.

With restoration work so dependent on sagebrush itself, TNC believes better seeding and planting techniques will ensure better success rates for the plants and wildlife. Plus, improved methods are in the American taxpayer’s best interests, as hundreds of millions of federal dollars have been spent to restore sagebrush habitat with a very low success rate.

So, obviously, the solution is Italian food. The Conservancy’s Oregon chapter has discovered an innovative approach that uses industrial-grade pasta machines to efficiently create packets of sagebrush seeds. The seed blend improves germination by creating a microclimate and lends a “power in numbers” approach, increasing the number of seeds that can break through the dry, hard soil. This work is just hitting the ground in Oregon, but TNC staff and partners are already looking at ways they can expand these efforts in places with similar challenges.

Meanwhile in northwestern Utah, a joint collaboration with five ranching families and NRCS has secured $3.7 million in public funding to protect 9,312 acres of sage-grouse habitat. One of the families involved, the Tanners, has received awards from the National Cattlemen’s Association and the Sand County Foundation for their leadership and work to conserve sage grouse and other wildlife. The Conservancy’s efforts to restore sagebrush habitat and increase sage-grouse populations would not be possible without this kind of collaboration with local landowners.

Grouse habitat encompasses millions of acres of private and public land. These magnificent birds function as primary indicator species for the health of their particular habitats, and they are held in especially high esteem by sportsmen and women, birders, biologists, and land managers. The North American Grouse Partnership works to bring the plight of all declining grouse species and habitats to the attention of the public, provides oversight for the health of grouse populations, implements solutions to the problems causing grouse declines, and encourages public policies and management decisions that will enhance important habitats and grouse populations.

RACs, the regional groups that help land managers balance multiple uses of public land, are allowed to start meeting again after a half-year hiatus, but there is a catch

Having partial ownership of 640 million acres is a unique privilege that comes with a huge responsibility, and that’s why you’ll often hear us say that sportsmen and women need to do more than simply keep public lands public. Quality management of America’s public lands requires balancing all the diverse demands on these lands.

This land belongs to all of us, and each stakeholder group—from hunters and anglers to ranchers and commercial interests—has its own distinct goals. This makes the grand ideal of multiple-use management pretty complicated to carry out on the ground. So, to make this juggling act work, land managers need to hear directly from local and regional interests.

Up until recently, one of our best channels for communication between locals and public land managers was temporarily shut down—we’re slowly getting back to the table to have meaningful discussions about how public land management impacts locals, but things have changed. Here’s what you need to know.

Public-land resource advisory councils—commonly known as RACs—are collaborative committees made up of individuals from diverse interest groups, usually with relevant professional knowledge, who provide input on management of the natural and cultural resources on public lands. Having served on the RAC for Bureau of Land Management lands in Southeast Oregon since 2015, I’ve been a part of a developing recommendations on land-use planning, motorized vehicle access, sage grouse conservation, recreation fees, wild horse and burro management, grazing, and fire projects.

The Department of the Interior oversees more than 200 individual advisory committees, including 38 RACs that meet with the Bureau of Land Management—the largest public-land management agency in the country. There are two other TRCP field staffers serving on full RACs in Idaho on New Mexico and weighing in on issues affecting BLM lands. Or they did, until their meetings were suspended.

Per instruction from the Department of the Interior, the BLM notified all RAC members in May 2017 that meetings would be postponed until at least September in order for the agency to review the “charter and charge of each Board/Advisory Committee.” Members could not meet to discuss pressing local issues, like sage grouse conservation, or get clarity on public lands issues of a national scope, like the review of certain national monuments.

In short: Those of us who have been passionate enough to devote our free time to collaborating on the best use of our land were effectively asked to stand down during a time of important decision-making.

In October, the suspension was lifted, and in Southeast Oregon, our full RAC has been able to have our first meeting back. But there’s a catch: Our subcommittee meetings are still not being scheduled, and since we can’t meet without approval from the national BLM office, our hands are tied.

Subcommittees might sound like a trivial thing, but they are where the action happens. These groups collaborate and compile detailed information and research on specific topics and pass recommendations along to the full RAC and district managers. Continued delay of the subcommittee meetings could mean a less effective RAC overall.

For example, I serve on the Lands with Wilderness Character Subcommittee. Before the suspension, we began some thoughtful discussions on land-use planning and possible management approaches to the district’s revised Resource Management Plan, a draft of which is expected in January. Our subcommittee’s feedback is not likely to appear in the draft, since we haven’t met to finalize any of our initial thoughts and recommendations—the final plan will guide the management of our BLM public lands for 20 years or more.

RAC members care about our public lands and public participation. This is a platform where diverse users come together, talk about our differences, and, more often than not, find common ground to forge agreements. The longer we go without proper meetings, the harder it is to say that federal land management agencies value our local perspective.

Really, we just want the chance to get back to work for public lands.

Like all members of the public, there is something we can do in the meantime—let our decision makers know where we stand. A great place to start is the Sportsmen’s Country petition to support responsible management of public land and wildlife habitat.

Once you’ve signed, tweet this: It’s time to do more than #keepitpublic. Add your voice at sportsmenscountry.org Share on X

The authority to modify national monuments lies with Congress alone, and this path throws into question the future of all monuments—including those created with the support of hunters and anglers

Today, President Trump announced his plans to use executive authority to reduce the size of Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears national monuments in Utah. The Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership expressed serious concern about the larger implications of this decision, especially considering the importance of national monuments to sportsmen and women as part of our uniquely American public lands system.

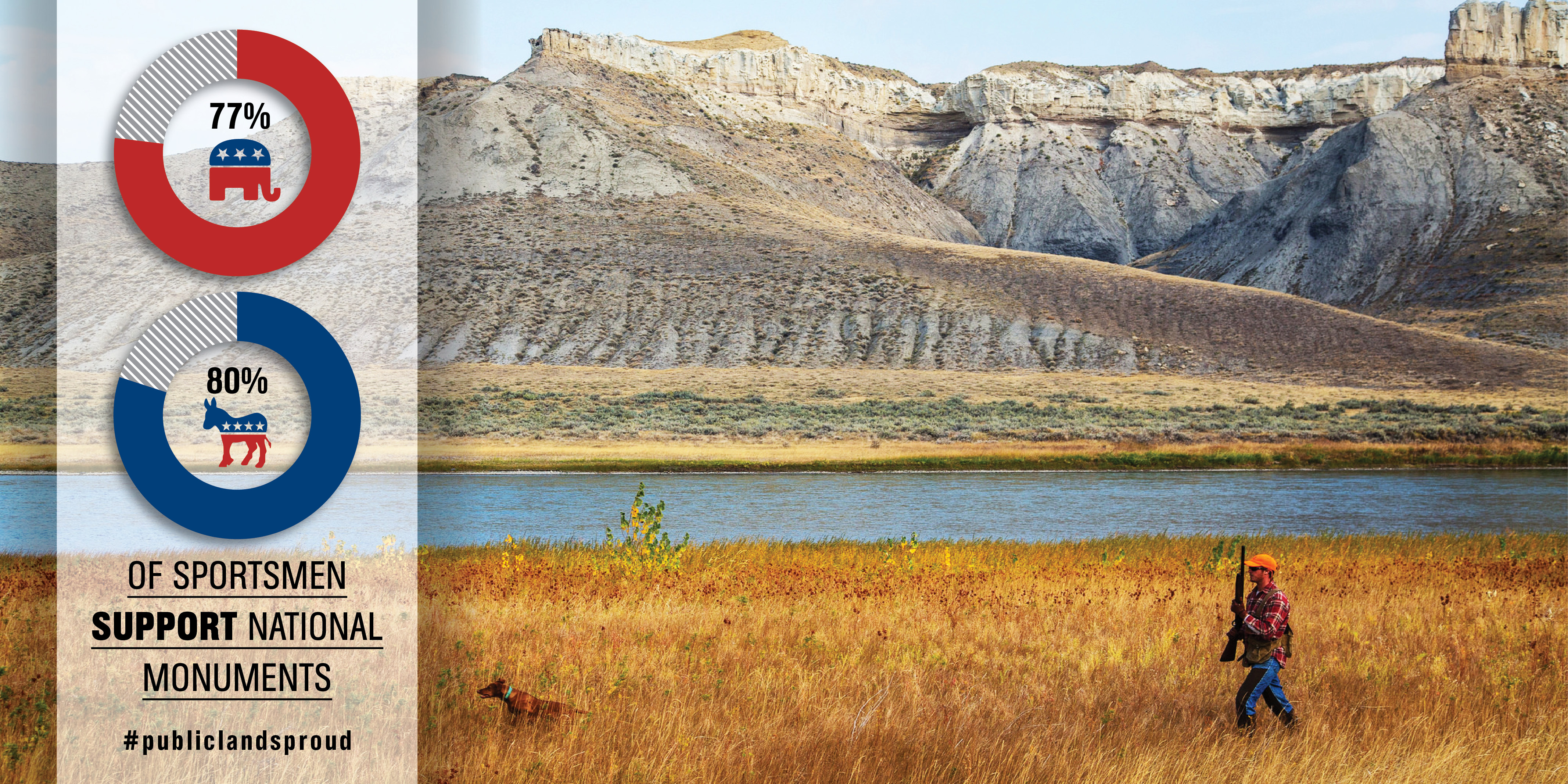

“There is a right and a wrong way to go about this, and the administration’s decision to skirt Congress in these decisions threatens to upend 111 years of conservation in America, putting at risk the future of any monument created under the Antiquities Act dating back to 1906, when President Theodore Roosevelt created Devils Tower,” says Whit Fosburgh, president and CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. A recent poll commissioned by the TRCP found that 77 percent of Republican and 80 percent of Democratic sportsmen and women support keeping the existing number and size of national monuments available for hunting and fishing.

While adjustments to national monument boundaries were made by the executive branch long ago, no president has attempted to do so in more than 50 years, and such decisions have never been tested in a court of law, according to the Congressional Research Service.

“If a president can redraw national monuments at will, the integrity of the Antiquities Act is compromised and many of America’s finest public lands face an immediate risk of exploitation,” says Fosburgh. “The power to create national monuments under the Antiquities Act lies with the President, and that authority is to be kept in check by Congress alone. We have repeatedly asked the administration to walk a path that upholds this precedent. Instead, the legacy of 16 former presidents, and the future status of some of America’s most iconic public lands, will be thrown into question.”

The future may also be uncertain for the numerous national monuments cherished by the sporting community, like those outlined in a report supported by 28 hunting and fishing organizations and businesses. More than 20 hunting and fishing businesses recently sent a letter to the White House encouraging the administration to “set an example for how the Antiquities Act should be used responsibly.”

Top photo by the Bureau of Land Management via flickr.

Former wildlife agency leaders, scientists, and other natural resource professionals warn that any changes to BLM’s sage grouse conservation efforts should be based on science and focused on the sagebrush habitat that supports 350 species

In a letter to Secretary Ryan Zinke, DOI staff, and the BLM today, more than 100 wildlife and natural resources professionals urged the administration to stick to the science when considering any changes to federal sage grouse conservation plans.

These professionals—each with ten to 57 years’ experience in wildlife and natural resources management, research, and conservation—came together to respond to the Bureau of Land Management’s intent to consider amending the current federal sage-grouse conservation plans finalized in the summer of 2015. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s landmark decision not to list greater sage grouse as threatened or endangered that same year was predicated, in part, on the effectiveness of these plans for millions of acres of the bird’s core habitat.

Many consider this to be the greatest landscape-scale conservation planning effort of modern times. “In the many years I worked as a wildlife agency director, I learned that strong cooperation between state and federal agencies is essential for successful wildlife management, and the collective compromise that kept the greater sage grouse off of the threatened and endangered species list is a shining example of wildlife management done right,” says Willie Molini, former director of the Nevada Department of Wildlife. “I believe that it would be best to let the existing sage grouse habitat plans work for a couple of years before any significant changes are considered.”

The letter asks that the plans be implemented and analyzed for effectiveness before they are altered. At the very least, the group would like to see the BLM exhaust all existing administrative methods of changing the plans before considering amendments that could delay or drastically re-chart the course for conservation. If amendments must be considered, they should be supported by science and maintain strong conservation outcomes for sage grouse. “We do not support weakening restrictions on development within priority habitat and feel any such actions would not be supported scientifically,” they write.

“We have a long way to go to keep that ‘not warranted for listing’ decision intact for sage grouse,” says Dr. Jack Connelly, a former wildlife research biologist with the Idaho Game and Fish Department, who spent most of his 41-year career working on sage grouse habitat issues. “Major changes, delays, or management actions that are not supported by the best-available science could threaten the entire conservation strategy that got us to this point—and that level of coordination and planning was an exceptional accomplishment.”

Hunting and fishing groups have been at the negotiating table in sagebrush country for years and recognize that some changes to the plans may be necessary. But a total overhaul of the plans would only serve a select few stakeholders in a diverse Western economy that has a lot riding on conservation outcomes.

“No land-use management plan—state nor federal—is perfect, so these plans should be improved upon over time,” says Dr. Ed Arnett, senior scientist for the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “Some changes to the plans may be acceptable right now, as long as they are science-based and don’t alter the entire course for conservation. We look forward to continuing to work with the Department of Interior and BLM to ensure sage grouse conservation is effective and also works for stakeholders across the West.”

The comment period on the BLM’s intent to consider amendments closed December 1. The agency will now begin analyzing feedback.

Read the letter from 105 wildlife and habitat experts here.

Signers include six former state agency directors, former U.S. Forest Service chiefs and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service directors, sage grouse scientists, habitat specialists, and wildlife biologists employed by state and federal agencies, universities, and non-profit conservation organizations concerned about the future of sage grouse and sagebrush conservation.

Top photo by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service via flickr.

From now until January 1, 2025, every donation you make will be matched by a TRCP Board member up to $500,000 to sustain TRCP’s work that promotes wildlife habitat, our sporting traditions, and hunter & angler access. Together, dollar for dollar, stride for stride, we can all step into the arena of conservation.

Learn More