Now that breakthroughs in wildlife research and GPS technology have taught us more about big-game migration corridors, we can’t ignore the value of these habitats—we have to conserve them

Wildlife management on public lands has benefited greatly from advancements in technology. In particular, our understanding of how and where big game species migrate has grown exponentially in recent years.

When I was a graduate student researching Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep in the late 1980s, satellite or GPS radio collars were simply not available. Back then, researchers had to capture their study animals, fit them with collars made with technology of that era, and follow animals around trying to determine their locations and habitat-use patterns.

Sometimes this meant three researchers all scrambling up to separate high points to triangulate where an animal was, using a telemetry receiver and antenna. Each one of us would determine the direction of the strongest signal emitting from the animal’s collar, aim a compass in that direction, and plot the bearing on a map. The place where our three lines intersected was theoretically where the critter was located. But times sure have changed.

No Compass, No Fuss

Today, advances in GPS telemetry are remarkable. Scientists merely have to catch the animals they’re studying to fit them with GPS collars that are accurate to within a few feet. No more worrying about triangulating compass bearings and human error—we know exactly where these critters are spending their time. GPS collars can also be programmed to mark multiple locations for each animal over any desired 24-hour period and automatically send this data to the scientist’s computer, tablet, or smartphone. Software has been developed that can sift through the data and build our maps for us.

Scientists now have the capability to build a travel log for the spring or fall journey of each antelope, bighorn sheep, or mule deer. Locations can be easily plotted in a GIS—a computer system for data related to positions on Earth’s surface—to create accurate, detailed maps showing where the animals traveled, how much time they spent in certain areas, and which habitats they preferred during these annual migrations between winter and summer range.

In Wyoming, scientists used this technology to follow mule deer 150 miles from the Red Desert to Hoback Junction, south of Jackson Hole, and transformed their research into a broader effort called the Wyoming Migration Initiative. Their goal is to advance the understanding and appreciation of Wyoming’s migratory big game species through science and public outreach, and they are currently working to expand to other Western states. This could help broaden the available data and build awareness among sportsmen and women, wildlife managers, and lawmakers across the region.

But the problem remains that our conservation policy and planning tools haven’t been updated, even as we’ve learned so much more, and these critical habitats are still largely overlooked.

The discovery of the Red Desert-to-Hoback migration corridor led the state of Wyoming to revise their policy definitions and develop a strategy for conserving vital migration corridors. This should help the Wyoming Game and Fish Department as they work with the BLM on conserving this often overlooked habitat, so it could be a model to follow.

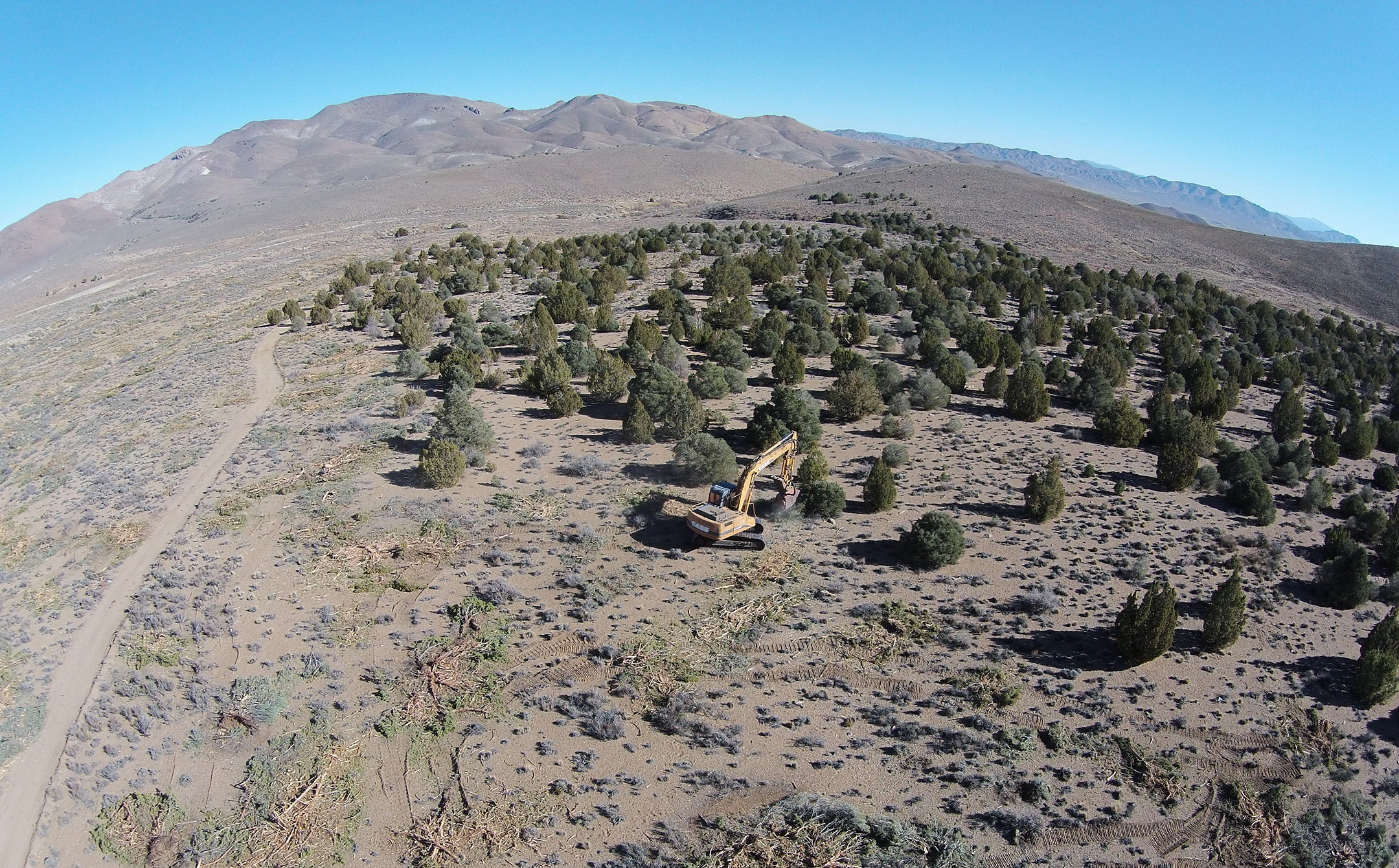

Hopefully these efforts will help advance conservation with good policy, because when migration corridors are not given this kind of attention, they may be damaged, developed, or lost from the landscape. Loss of these corridors could have drastic impacts on big-game herds, hunting opportunities, and the outdoor recreation economy.

Time for a System Upgrade

All of the fancy data and maps in the world would be pointless without adequate policy and management actions to conserve the migration corridors that we now understand are important for big game species’ survival. We need to use what we’ve learned to ensure that the iconic big game herds of the west can be sustained well into the future.

Now that mule deer can literally send scientists mobile notifications of their whereabouts and preferences, it’s time for a policy upgrade based on this new information. It’s not enough to maintain and restore the habitat where wildlife spend most of their time, especially if degraded habitat conditions along migration routes can prevent them from getting there.

It is not enough anymore, either, for sportsmen and women to simply fight for keeping public land public. It is critical that hunters and anglers get involved in public land management decisions that could help accomplish more, like conserving migration routes and stopover areas.

Improving the management of our public lands will undoubtedly be a long journey. Sign the petition at sportsmenscountry.org to take the first step.

Top photo by John Carr/USFWS via flickr

This story was originally published February 25, 2016 and has been updated.

Can’t agree more. Science is only as good as the action upon which it spurs.