Opening New Mexico’s Sabinoso Wilderness has given sportsmen and women tremendous new opportunities, but support for one conservation tool will be critical to future access wins

When it comes to conservation success stories, we have an embarrassment of riches here in New Mexico. Just last year, we saw the establishment of legal access to the 16,000-acre Sabinoso Wilderness, which until last year was entirely surrounded by private land with no public roads or trails across. Now open to all, this national treasure offers an abundance of opportunity for hunters in pursuit of mule deer and turkey.

The unlocking of the Sabinoso required considerable effort by private individuals, conservation groups, and public officials from both parties. It is an accomplishment and a landscape well-worth celebrating, and has truly deserved the attention it has received in the press. In the wake of these triumphs, however, it’s important not to lose sight of the challenges in front of us.

I was reminded of this point at a recent event to recognize the conservation achievements of our two U.S. senators, Martin Heinrich and Tom Udall, who each played a critical role in the Sabinoso story. At an event to honor their past contributions, both seized the moment to voice their full-throated support for renewing the Land and Water Conservation Fund in perpetuity. They clearly see the potential expiration of this law, should Congress fail to act before September 30, as the issue of the moment for sportsmen and women.

Since its inception in 1964, the LWCF has been the United States’ premiere conservation program. By diverting a small percentage of federal royalties from offshore oil and gas leasing, it has invested more than $16 billion in conservation and outdoor recreation, including the establishment of public fishing areas, new access into landlocked and checkerboarded parcels of public lands, and the acquisition of lands and waters for the benefit of fish, wildlife, and the sporting public. Its record of success leaves no doubt that it is the best-available instrument for fulfilling the administration’s commitment to recreational access. As both Udall and Heinrich noted, the LWCF enjoys very strong bipartisan support in both houses of Congress and—given that it costs the taxpayer nothing—all across the country.

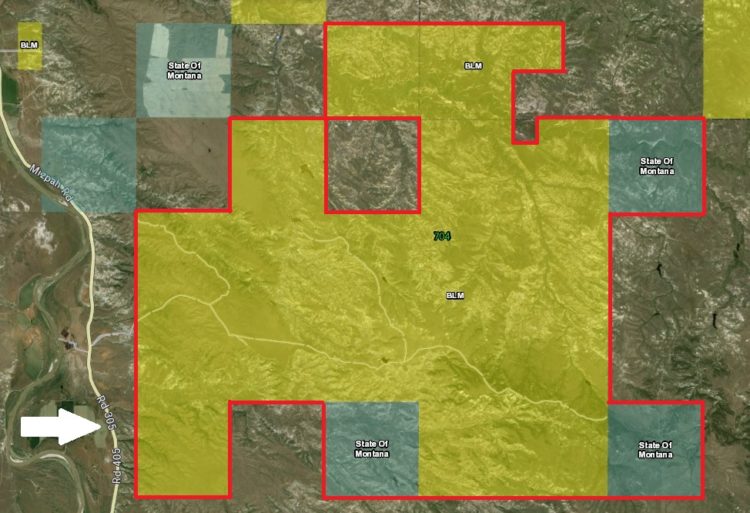

In New Mexico, we know that this powerful tool is capable of doing a great deal of good. From 1964 to 2015, there have been 1,024 projects amounting to $42,406,844 spent on everything from municipal ball fields to state parks. We’ve benefited enormously from the LWCF, which also funded the purchase of the 80,000-acre Valles Caldera (pictured above) from a private entity. Now managed as a national preserve, it offers some of the best hunting and angling in the West. Elk hunts and turkey hunts are offered through a public draw and the trout fishing is second to none. The preserve also generates revenue through their livestock-grazing leases.

The LWCF has an incredible legacy, to be sure, but it has a promising future as well. Who knows how many new success stories we’ll have to tell in the years ahead, or how many opportunities will be created for generations of sportsmen and women yet to come? In landscapes like the Sabinoso and the Valles Caldera, I see both the payoff for past efforts and also enormous potential for the work ahead.

Hearing such strong commitment at last month’s gathering left me encouraged. For someone who understands the importance of the Land and Water Conservation Fund, it is reassuring to know that there are some politicians working to address sportsmen’s concerns in Washington, D.C. But their voices and votes won’t be enough when push comes to shove on the reauthorization this fall. Take a minute and let your elected officials know how important the LWCF is to conservation and to the future of our hunting and fishing traditions.

Top photo courtesy of BLM New Mexico

Second photo courtesy of Larry Lamsa

I have yet to have the great pleasure of visiting the Sabinoso Wilderness but look forward to someday. However the author cites elk hunting opportunity as a benefit – there exists no public land elk hunt for this unit. Just thought I should clarify.

Thomas, thank you for pointing that out! The Sabinoso is not in a unit that is open for a public elk hunt but now that we have sportsmen’s access maybe it’s a future possibility.