Why isn’t the USDA leaning more heavily on native grassland restoration to save this and other iconic species?

“I haven’t seen one of them around here in years.” Whether you’re talking to farmers or wingshooters, this statement about bobwhite quail is as familiar and repeated as the bird’s distinct whistle: bob-WHITE! bob-WHITE!

Across Texas rangelands and southeastern pine forests historically ample quail habitat has declined over the last half century. Unfortunately, the story of bobwhites—once one of the most important game species in North America—is representative of a greater issue all too common in the world of wildlife conservation. The iconic game bird has effectively been forced into a patchwork of suitable habitat, all but removing our opportunities to chase that distinct whistle across the bird’s historic range.

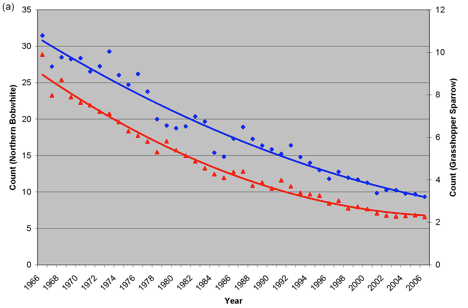

Ornithologists at Cornell University have labeled the bobwhite quail a common bird in steep decline, an appropriate moniker given their finding of a steady 4-percent annual population decline—that’s an 85-percent drop since 1966.

The “why” of it all is well agreed upon at this point: land conversion. The steady creep of development, monoculture cropland, edge-to-edge farming, and pesticide use has contributed to the slow-motion erosion of the diverse habitat required to sustain populations of bobwhites.

The below graph by the National Bobwhite Conservation Initiative illustrates the trend.

Part of the challenge facing species recovery efforts is that gentleman bob has very particular tastes when it comes to habitat. Quail are ground-nesting birds that require a mix of seasonal vegetation. During colder months, coveys huddle in dense shrubs and grasses, and in the spring and summer, they opt to nest, forage, and brood in tall forbs and grasses that provide lush groundcover, shade, and security from predators. Quail need to feed on a diversity of seeds, fruits, and bugs in these grasses but escape to woody brush when they catch the eye of a hungry predator—all within 12 inches of the ground.

Understanding the fastidious nature of bobwhites is essential to the successful establishment of sustainable quail habitat. This has led groups like NBCI, which leads the way on bobwhite recovery, to support the adoption of native grasses into grassland restoration. In 2018, the TRCP worked with several of our partners to include official language encouraging the use of native grasses for the very first time in established Farm Bill conservation practices.

But that work is far from done. This provision was included in a Committee Report, which establishes a degree of congressional intent, but it holds little more weight than a suggestion as the U.S. Department of Agriculture moves ahead with implementation of the Farm Bill. Currently, several private land conservation programs only support the establishment of the “lowest practicable cost perennial conserving use cover crop”—whether native or non-native—which may sustain some species and benefit soil health, but is not guaranteed to provide the quality cover habitat required by bobwhite populations.

For these reasons, the TRCP was proud to join a handful of our conservation partners to become part of the Native Grasslands Alliance. Together, we’ll coordinate policy and communications efforts in support of increasing the adoption of native grasses and vegetation on both working and retired public and private lands.

The establishment of native vegetation is not only critical to the recovery of bobwhites, but also to address collapsing populations of songbirds, monarch butterflies, and other pollinators in recent years. The continued reliance upon introduced grasses in USDA programs runs counter to other ongoing efforts to restore these species. It begs the question: Is the public interest being accounted for when native grasses are forgone for the sake of economic ease?

One thing can be sure, a return to the huntable bobwhite populations of years past will not be achieved without a sea change in how American agriculture approaches grassland conservation and restoration.

I am totally with Mr. Andrew Earl the whole way, restoring native grasses and limiting land development are just two of the much needed answers. Some people would develop every spoonful of ground, if they could. Just leave it alone.

Not only do individual landowners need to leave some suitable quail habitat, they need to urge their neighbors to do the same so they don’t become an island of habitat that’s not interconnected with other suitable quail cover nearby.

quailforever.org is a great organization with many aligned partners that are setting the standard for quality habitat across the landscape

Hi, to which organizations can we make monetary contributions to save bobwhite habitat?

Thanks for your interest, Richard. This is a good place to start: https://bringbackbobwhites.org/donate/

Quail Forever dedicates itself to habitat conservation and is working hard with partners to improve habitat on both private and public land in Texas.

WE needs to preserve our natural resources for wildlife to survive.

Great article. It’s really encouraging to hear this talk about habitat restoration across several groups. I would love to see quail populations come back to what they were when I was a teenager. Most fun you can have with your boots on. I guarantee it!

In 2014 I converted a cow pasture that was planted in Bahia grass into native grasses for quail. It has been truly stunning how it quickly became almost overrun with quail. To me it is a classic example of what can be done if you want wild birds. Glad to share with anyone how it was done.

Here in IL we have many large farms, but also have many small tracts if less than a couple hundred acres. We need to incentivize those smaller tracts with programs. Many large farms don’t have habitat restoration on the radar. It’s profit first, and some make a very good living already. The smaller landowners are where you will have the most program success. Need really good communication programs on them as well.