Hint: Consult your U.S. History books for the answer

Working with conservation policy sometimes makes clear how much you may have forgotten from grade school, like biomes, basic watershed ecology, government checks and balances, and “I’m just a bill and I’m sitting here on Capitol Hill…” And in partnering with onX to identify landlocked public lands across the country, we’ve been reminded of a few U.S. history lessons.

Our country’s unique past has shaped land ownership today—from the creation of a much-celebrated national public lands system to the American Dream of individual home ownership to the boom and bust cycles across various industries. The resulting mosaic of county, state, and federal land holdings in the U.S. has also left a remnant patchwork of isolated public land parcels with untapped opportunity for hunters and anglers.

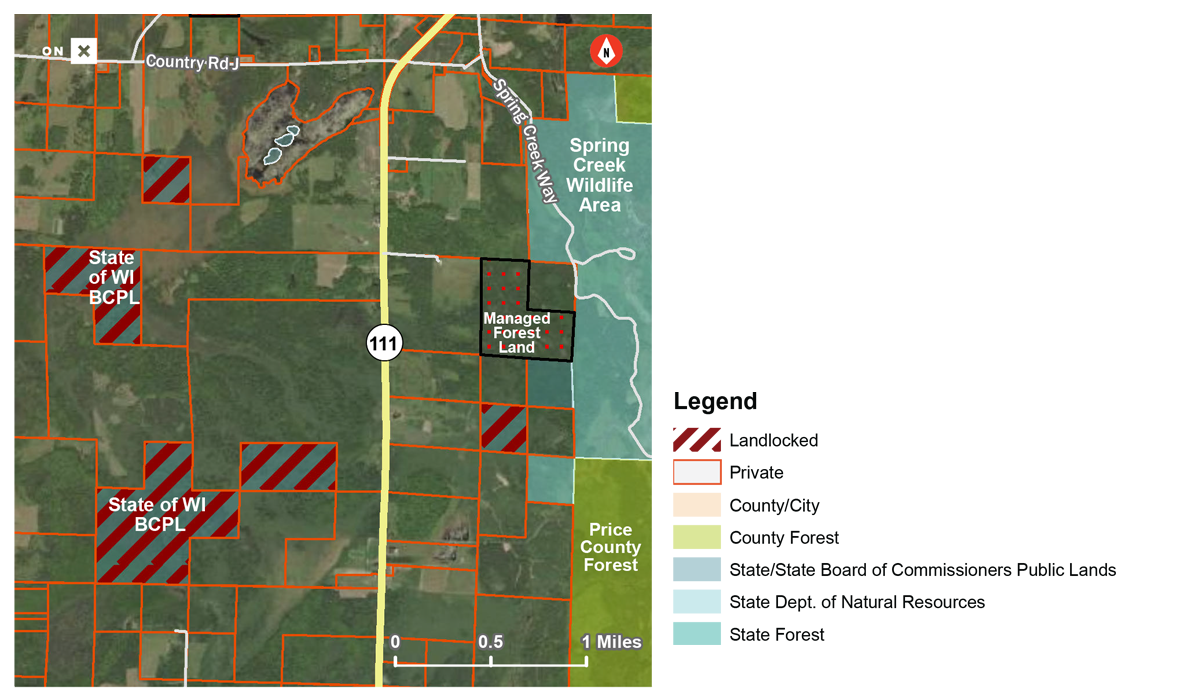

Westward expansion, homesteading, and the railroads would lead to checkerboarded federal and private lands in states like Wyoming, Montana, and Nevada. In the Upper Midwest, some land conveyances were made to either expand agriculture or retire marginal farmlands, and plenty of private lands went back to state or county and municipal ownership through tax forfeiture.

But in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic region, there were different contributing factors.

Lay of the Landlocked

Given their history as British colonies, the original thirteen U.S. states were not organized according to the gridded system of ranges, townships, and sections later used to parcel out land ownership in new states and territories as the country expanded westward. As such, property boundaries in states like New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania were drawn around geographic features and other landmarks through an early survey system known as “Metes and Bounds.”

Nearly all land in these states became private property during the colonial period through charters granted by the British Crown to corporations or individuals, as well as through the sale of Crown lands. It was only much later that these states—faced with depleted soils, diminishing timber stands, and deteriorating water quality—began actively purchasing lands to address conservation, access, and resource management needs.

The Difference Between East and West

Though they are dwarfed by the sheer land mass of Western states, some Eastern states have accumulated rather large amounts of public land. In New Jersey, the state owns 21 percent of the land within its borders, the third-most of any state behind Alaska and Hawaii. In New York and Pennsylvania, those figures are similarly significant: 14 percent and 13.9 percent respectively, at fifth and sixth place in the nation.

Managed for varying purposes and according to a diverse set of frameworks, public lands in these three states have a rich tradition. New York established the first state park system in 1881 and created the Adirondack Preserve (later Adirondack Park) in subsequent years. New Jersey similarly has its own large, relatively undeveloped, and sparsely populated natural area in the state’s southern Pine Barrens.

Many of the state lands in the region, particularly in New York and Pennsylvania, were formerly abandoned farmlands or private timberlands on which the owners stopped paying property taxes after the parcels were cut over in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Other lands were acquired by the states to conserve wildlife habitat in the early 20th century. The Pennsylvania Game Commission, for example, manages nearly 1.5 million acres of State Game Lands for this purpose.

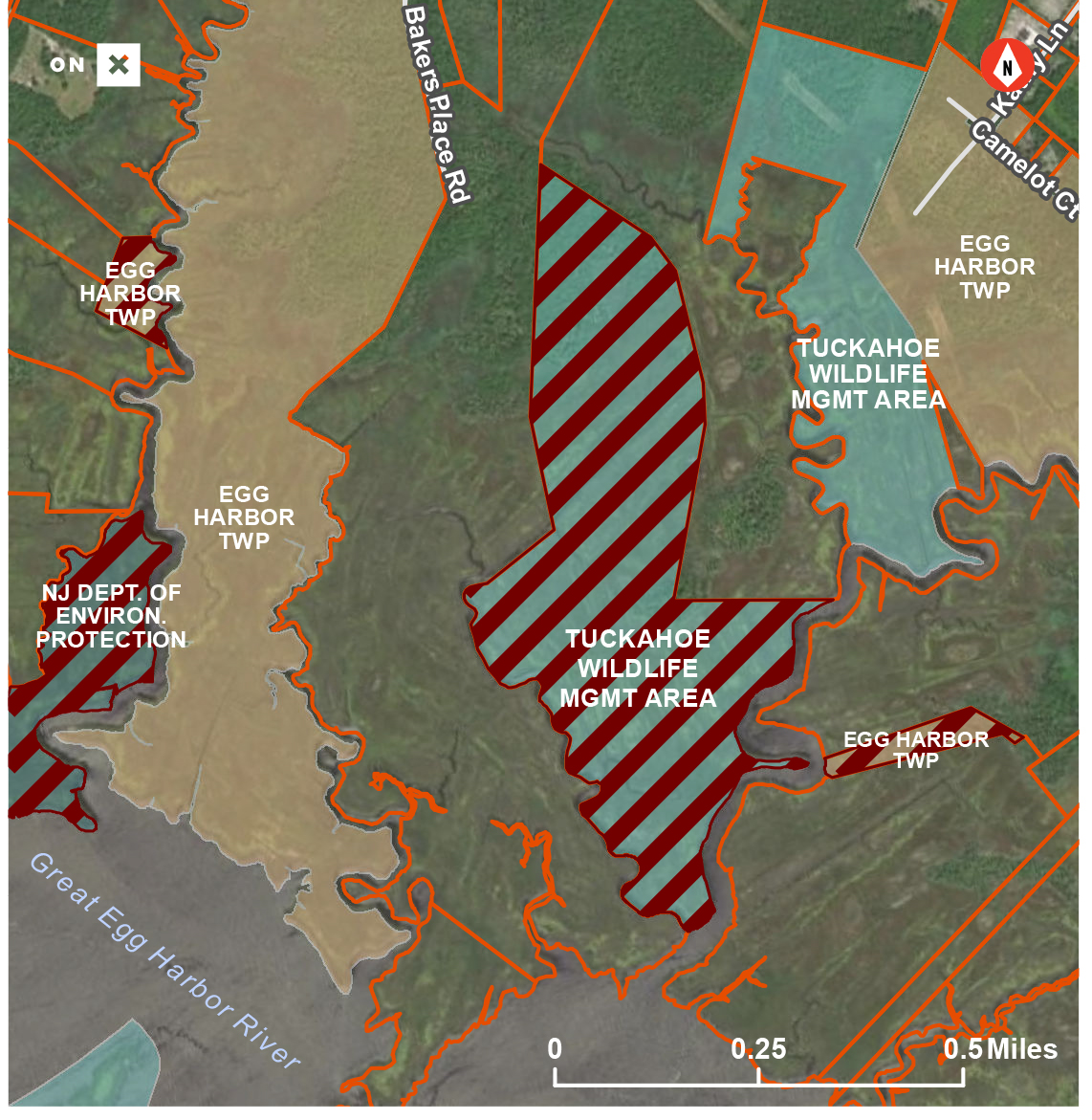

Accordingly, the bulk of the 80,000 acres of landlocked public lands we identified in the Mid-Atlantic are managed by the states, counties, and municipalities. Less than 5 percent of all the landlocked acres we found in this region are managed by federal agencies, compared to about 60 percent in the West.

Another important distinction between East and West, because land ownership boundaries in this part of the country are far less likely to align neatly at corners like a checkerboard, is that “corner-crossing” as a contested form of public access is a much less significant debate in the Mid-Atlantic states.

That doesn’t diminish the severity of having 80,000 acres of lost hunting and fishing opportunities across the region. There are solutions, but sportsmen and women must be vocal about the resources and legislative initiatives necessary to unlock our public lands.

Dig into more of the landlocked data at unlockingpubliclands.org.

Top photo courtesy of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation via flickr.

love the info, did not realize that public land was still being landlocked, last time i was working in the clear lake area, there was public access areas that were “closed” by the neighbors this was in the s.w. portion, would /can you ck this out too? keep up the good work thanks tom

Thanks, Tom! Tell us as much as you can about this issue here: https://www.onxmaps.com/landlocked-public-lands/report-a-land-access-opportunity

Leave the last untouched lands alone. Man doesn’t need to ruin every square foot.

We appreciate the opportunity to hear your thoughts, Christine. These are not wilderness areas simply because they’ve become surrounded by private lands. They are owned by federal, state, county, or municipal agencies and some are even managed primarily to generate revenue to fund schools and other institutions. Thanks for reading.

I just put a complaint in with DNR in Washington State. They have allowed private land owners to put gate’s everywhere. Which has cut off access to our state public land’s. Which up until the last 10 year’s never had gate’s blocking our access.