When it comes to public lands mapping data, sportsmen and sportswomen deserve a higher standard

Most recreational access opportunities on public lands are identified in agency management plans and may appear on agency-produced paper maps that show, for instance, roads and trails open to different types of motorized and non-motorized vehicles. Sometimes alongside a national forest road you’ll see a sign marking a zone where hunting or shooting is restricted, such as near a campground or forest service ranger station. Other times you’ll pull up to a mountain lake parking lot and a sign is posted that specifies horsepower restrictions for boats.

While some of this information might, in certain places, be available in a GPS-compatible format, in many places it is not. As a result, it is difficult for the public to find specific information about available recreation opportunities on public lands or even follow the rules that the agencies have spent millions of dollars creating. Sometimes, a person might avoid hunting in an area altogether simply because they can’t tell by looking at a sign where the no-shooting boundary starts and ends. Many members of the public might also avoid driving on an open road because the existing sign long ago went missing and they don’t want to inadvertently break the rules.

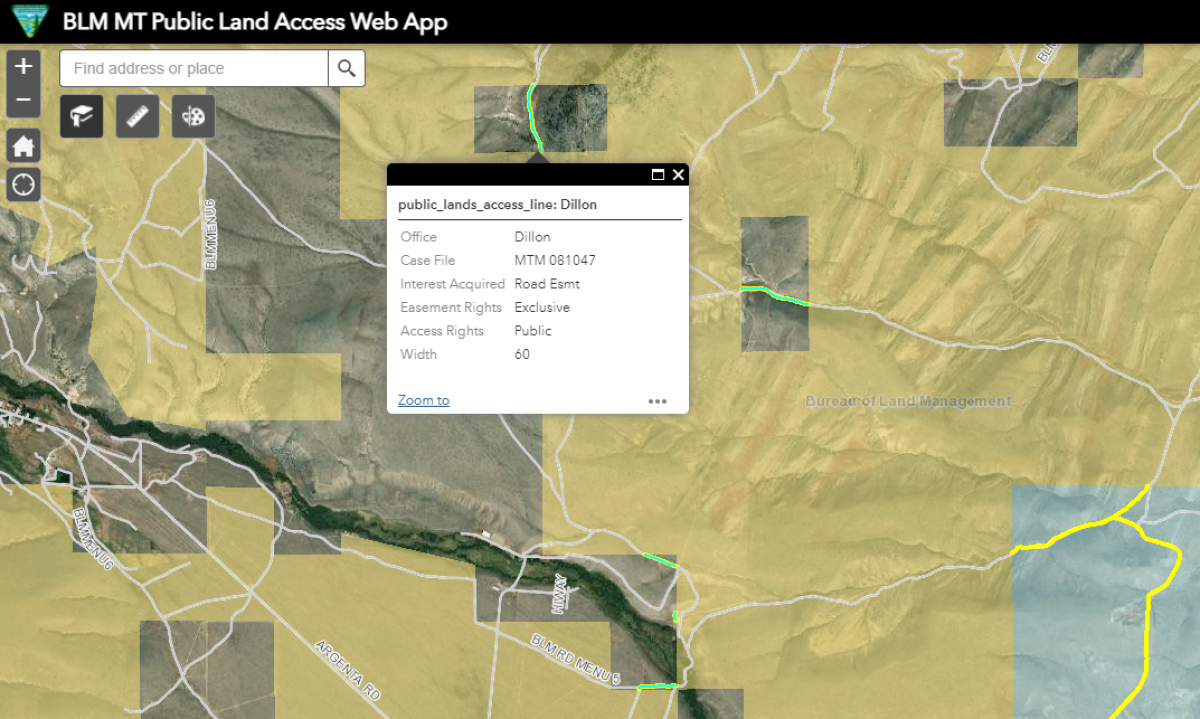

Where geospatial data layers have been made available by the agencies, they are not all designed to benefit recreational access to the extent that they could and should. For example, in 2015 the BLM created a national transportation layer called the Ground Transportation Linear Feature data standard, or GTLF, which is a digital mapping layer that delineates BLM-administered travel routes. The GTLF, however, doesn’t provide enough information for the public to understand access opportunities and restrictions because it does not require attributes for allowed vehicle type and seasonal restrictions. As a result, the investment that went into this dataset is ultimately lost on hunters, anglers, and most other recreationists.

A case in point can be found in the BLM Butte Field Office in southwest Montana where the agency completed a travel management plan (TMP) for the Upper Big Hole area in 2009, which established comprehensive rules for vehicle travel on specific routes and during specific times of the year. In this place, the local BLM field office did a good job with their travel plan in that it provides adequate public access while conserving important deer and elk habitat. However, because the national GTLF is lacking in important attributes, detailed transportation information for the Upper Big Hole area can only be found by those with the skills to locate and review an environmental impact statement. Under these circumstances, an elk hunter in the area wanting to understand and follow agency transportation rules must rely on good signage on the ground—a difficult thing for the BLM to maintain with limited budgets and considerable miles of roads and trails.

This challenge is not limited to Montana. The BLM has completed travel management planning on approximately 20 percent of the 245 million acres administered by the agency, yet useful geospatial transportation data is not publicly available for most areas. In fact, the only places where helpful geospatial transportation information has been made available is where local BLM offices have taken it upon themselves to develop more thorough transportation layers than required by the agency.

The MAPLand Act would fix this information shortfall by requiring the BLM to add access specific attributes to the GTLF and make them publicly available within three years. GPS mapping companies could then add these data to their smart phone applications and make detailed access information available to the public in real time.

While each agency can point to some accomplishment of the mapping requirements proposed in the MAPLand Act, their data are generally inconsistent from one agency to the next and none of the agencies have completed all of these proposed requirements. For example, the USFS has done a really good job with its transportation layers, while other agencies like the Bureau of Reclamation have considerable work left to do. Without consistent and comprehensive data provided by each agency, hunters and anglers can’t be confident that GPS mapping devices will provide them with the information they need to stay safe and legal while recreating on public lands.

There are also useful data layers that MAPLand would require the agencies to produce that are currently not being pursued. For instance, there is no comprehensive digital information being developed for areas with shooting restrictions, nor is there standardized digital information on watercraft rules. While management decisions regarding these recreational opportunities have been made in agency land use plans, the creation of digital resources for the public has been overlooked.

Agency personnel and a variety of stakeholders invest considerable time in the public processes used to create these management decisions and frameworks, which ultimately aim to conserve the values and resources held in trust for all public landowners. But unless the resulting plans are easily accessible to everyone—which in the twenty-first century means available with a glance at a smartphone—we aren’t seeing the full benefits of the hard work and collaboration that went into creating them.

It’s time that our federal land management agencies have the guidance and funding to bring public land mapping systems into the modern era. Public land users of all types should be able to use digital mapping systems and smartphone applications to identify new opportunities for access and recreation, and to better understand the rules to help reduce conflicts with private landowners and prevent inadvertent violations of agency regulations.

Top Photo: Maven/Craig Okraska