Hunters, ranchers, and land managers partner for the benefit of wildlife and working lands

As snow recedes in the Centennial Mountains along the Idaho-Mountain border and in the high country of Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks, big game animals are on the move.

Following the spring green-up that comes with snow’s retreat, roughly 10,000 deer, elk, moose, and pronghorn are leaving the Sand Creek winter range—located roughly 50 miles northeast of my home in Idaho Falls— and heading primarily north and east to the high-country headwaters from Camas Creek east toward Yellowstone’s Boundary Creek and Falls River.

The seasonal movements of these animals are one of the wonders of the West, especially considering the challenges presented by habitat lost to severe wildfire, the proliferation of fences and other barriers, and the near-constant encroachment of more second homes, roads, and major highways. With Idaho’s rapid growth in recent years, keeping this migration route intact will be a major challenge.

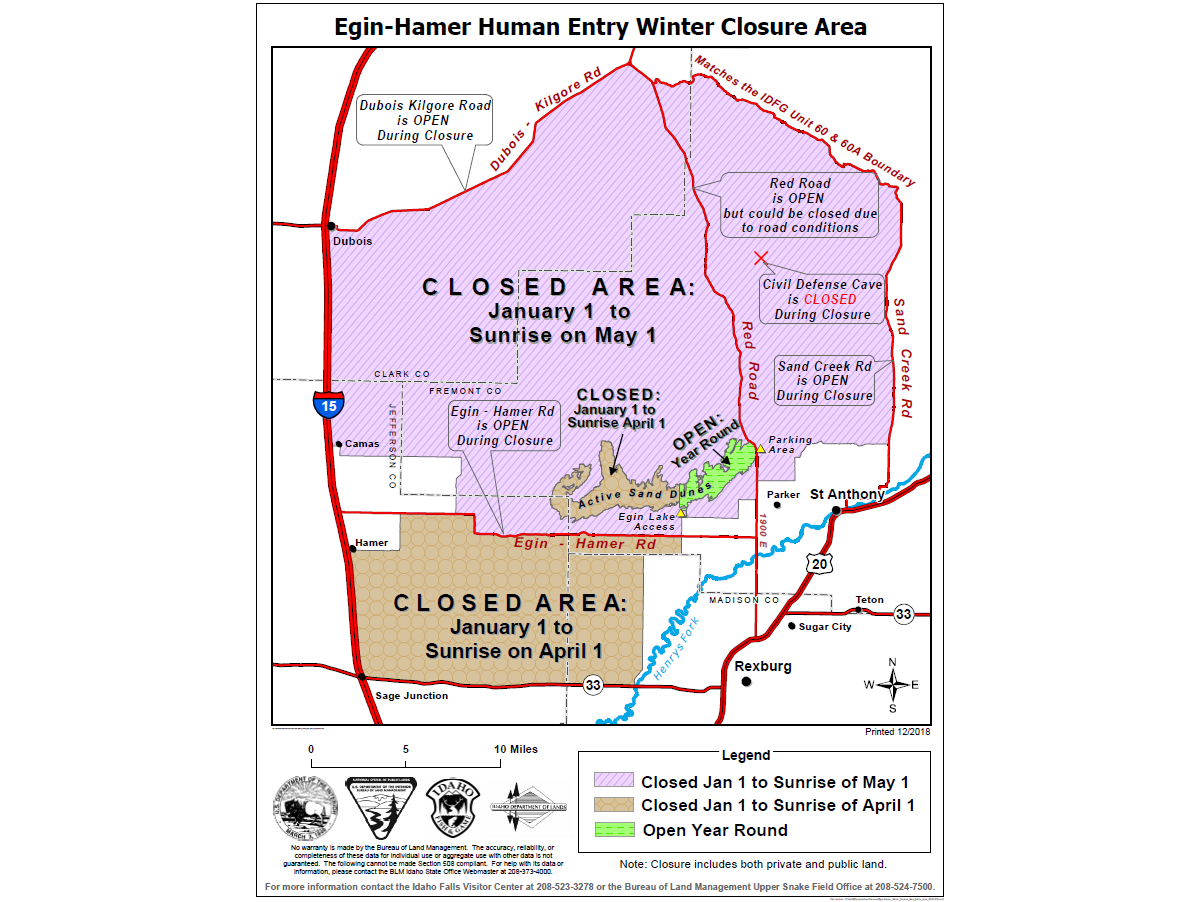

Fortunately, a blueprint for success has been developed at the wintertime terminus of this major migration, the Sand Creek desert, which sits between the towns of St. Anthony and Dubois in eastern Idaho’s Fremont and Clark counties. The winter range is a 500,000-acre patchwork of Bureau of Land Management public lands, endowment lands managed by the Idaho Department of Lands, and private property.

Despite the differences in priorities of the various stakeholders, these agencies and landowners have teamed together to conserve the winter range while also allowing the local ranching industry to thrive.

The partnership began in the 1970s when local ranchers applied to have 4,000 acres of big game winter range converted to cultivation for potato farming. The BLM rejected the proposal, but the ensuing dialogue resulted in the Sand Creek Habitat Management Plan, adopted by the BLM, Idaho Department of Lands, and Idaho Department of Fish and Game, which outlined a cooperative management approach to enhance the elk winter habitat in the BLM’s Sands Habitat Management Plan. One of the plan’s main goals was to help a fledgling herd of elk that was first identified in the area in 1947, and, in the late 40s or early 1950, the Fremont County Sportsmen Association also transplanted 12 elk to the area from Yellowstone National Park.

The partnership was tested in the 1980s when local ranchers and the counties asked the BLM to turn the Egin-Hamer Road into a year-round, farm-to-market road. Again, the local landowners lost their request at first, but cooperation won out in the end. In exchange for converting the road into a year-round thoroughfare, all of the interested parties agreed in 1987 to an annual closure for the winter range that limited all human entry from Jan. 1 to May 1, preventing human disturbances to big game animals already stressed by harsh seasonal conditions. It is a model of conservation that came to pass because of cooperation and negotiation.

More than 30 years later, the group of agencies, landowners, and sportsmen that created the wintertime closure are back at the table, working for the best interests of wildlife and the local ranching community. Mobilized by a 2019 wildfire that burned roughly 20 percent of the winter range, conservationists, sportsmen, landowners, state biologists, and federal land managers have joined forces yet again. This time, the priority is to build firebreaks to protect the remaining healthy winter range and design vegetation treatments to restore the overgrown stands of aging sagebrush. The goals of their collaboration are preventing large wildfires, improving wildlife habitat, and providing for a working landscape.

Already this spring, deer, elk, moose, and pronghorn have largely left the Sand Creek Desert, riding the green wave of new forage to the high country of the Centennials and Yellowstone. There they will calve and fawn. They will fatten over the summer and fall until deep snow pushes them back down from the mountains. The winter range will be waiting, protected by meaningful conservation safeguards, and in the good hands of Idahoans who are working together.

Sand Creek is a template for how to manage challenges facing winter ranges and other valuable wildlife habitats. More importantly, it is a model of the type of cooperation that has been at the heart of our country’s greatest conservation successes. That same collaborative spirit will be needed on future BLM and Forest Service planning efforts as we continue our work to ensure the West’s big game herds can move between the seasonal habitats they need to thrive.