Whole Crew

Do you have any thoughts on this post?

Washington, D.C. — In a 221-201 floor vote today, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the INVEST in America Act, a five-year highway bill with much-needed funding for fish and wildlife habitat connectivity, climate resilience, and road and trail maintenance across public lands.

The Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership is particularly encouraged to see the advancement of a new $100-million-per-year grant program that would help states construct more wildlife-friendly road crossing structures, including over- and underpasses, that benefit migrating big game and many other species. An amendment was also successfully passed to establish a new grant program to fund and support culvert restoration projects, which will help restore essential anadromous fish passages across the nation.

“It’s the right time to invest in America’s transportation infrastructure and jobs, and it’s highly appropriate that we look out for fish and wildlife habitat as we make largescale improvements,” says Whit Fosburgh, president and CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “This may be our best chance to knit together fragmented migration corridors and fish habitat, especially now that we know more about the way animals use seasonal habitats and exactly how development affects their movement patterns. The science and technology have advanced, but we can’t create solutions without the dedicated funding provided in this bill, which would create the first national wildlife crossings initiative of its kind and help prioritize culvert restoration across the country.”

The bill also includes an amendment that authorizes the Legacy Roads and Trails Remediation Program through 2030 and requires the U.S. Forest Service to develop a national strategy for using the program—which would have a direct impact on public land access and hunting and fishing opportunities on Forest Service lands. The Forest Service also gets a share of the $555 million per year included in INVEST for the Federal Land Transportation Program, but the TRCP and partners will continue to push for more balance here.

Importantly, INVEST would also:

The Senate surface transportation bill includes the culvert provisions but only $350 million over five years for wildlife crossings. It also includes a climate resilience program that is not in the House bill. The two versions will need to be reconciled before the president can sign off and advance the much-needed conservation provisions mentioned above.

Top image courtesy of the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources.

Once again, the pendulum is swinging back toward protection of our nation’s streams, rivers, and wetlands – and thus the fish, waterfowl, and other wildlife that rely on these waters.

On June 10, the Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps of Engineers announced that they would reconsider which waters and wetlands should be protected under the Clean Water Act, which is now 49 years old. The definitional rule, referred to as “Waters of the U.S.” (WOTUS), describes which discharges to our nation’s waters and wetlands need permits and, therefore, protective conditions.

Discharges potentially needing permits are both from “point sources,” like wastewater treatment plants and factories, and from development activities, like the construction of dams, diversion structures, roads, bridges, or tracts of houses.

The rule the agencies have committed to repeal and replace was issued in April 2020. It shrunk the wetlands protected by Clean Water Act programs by millions of acres, and the number of stream miles by as much as half. (The agencies do not have precise figures for the rule’s impact.) While there had previously been changes to the range of waters and wetlands that the law governs, those changes were never previously more than a few percentage points. The agencies have now conceded in legal challenges to the 2020 rule that there were over 330 construction projects poised to proceed without permits, i.e., without any mitigation for water quality required.

The potential impact to critical fish and wildlife habitat is frightening. Maybe it is because of our interconnectedness with rivers and streams that, according to a 2018 poll commissioned by the TRCP, 92 percent of hunters and anglers were in favor of strengthening federal clean water protections. That makes us possibly the most supportive demographic in the country.

Last month, my colleague Andrew Earl wrote about the failure of the USDA to protect wetlands in the prairie potholes region of the Upper Midwest—the nation’s “duck factory.” These same wetlands sometimes qualify for protection from being filled with construction dirt under the Clean Water Act, but they were entirely excluded from protection under the 2020 WOTUS rule.

Now more than ever, as migratory birds face the loss of habitat due to climate change, all of our government’s agencies should be working to conserve wetlands using every arrow in the quiver.

The administration has promised a robust stakeholder process to develop a new definition of WOTUS, one that the TRCP hopes would be durable enough to withstand the swings of the political pendulum. That process will take time. The administration has already asked the courts reviewing challenges to the 2020 rule to pause their considerations so that the agencies can make changes.

The next step for the agencies must be to repeal the 2020 rule outright and reinstate the coverage that the George W. Bush administration put into place in 2008, following a U.S. Supreme Court ruling on WOTUS. That will at least restore wider coverage and perhaps forestall some of the hundreds of habitat-damaging projects that might otherwise proceed.

The current administration must do this repeal as quickly as possible, in part because any “jurisdictional determination” the Corps makes until the rule is repealed would last for five years. That means a project may proceed without a permit without being revisited for half a decade, even if there’s a replacement rule put into place in 2024.

The TRCP appreciates that the agencies want to get a new rule right, so that it can withstand judicial review, and that doing so will take some time. But they cannot be too cautious with the repeal. Without it, too many destructive projects may proceed, and the loss of wetlands and streams is not something easily reversed.

Continue following the TRCP to be the first to know about opportunities to engage in the effort to restore Clean Water Act protections to headwaters and wetlands.

Top photo courtesy of USDA NRCS Montana via Flickr.

Our work at the TRCP is grounded in partnership and the goal of uniting and amplifying the voices of sportsmen and sportswomen who share a commitment to the future of America’s legacy of conservation, habitat, and access.

In that spirit, this spring we worked with Colorado Parks and Wildlife as well as a Colorado-based nonprofit consultancy, the Meridian Institute, to host a stakeholder roundtable of Latino hunters and conservationists with the aim of better understanding how state fish and game agencies can more effectively engage with this growing community.

As one of the top three fastest growing populations in the United States, the Latino community has an important role to play in the future of our country’s hunting and conservation traditions. This is especially true in Colorado, where the Latino population is expected to grow from 20 percent to 33 percent in the next 20 years, and 77.2 percent of those individuals are native-born Coloradans. Nationwide, Latinos indicate that they regularly participate in outdoor activities: 77 percent hike, 46 percent camp and 33 percent hunt and fish. Latinos polled in Western states also strongly support conservation:

These shared conservation values were central to the roundtable’s work. Participants had diverse backgrounds and levels of experience with hunting, ranging from lifelong, multi-generational hunters to participants with an interest in becoming a hunter but who face systemic barriers as they try to enter into the hunting community. The roundtable discussions were informed by an assessment by TRCP of retention, recruitment, and reactivation (R3) programs in several states: Colorado, Texas, Florida, and South Carolina.

The goals of these convenings were to identify opportunities, challenges, and tangible recommendations for how CPW and other state wildlife agencies can enhance its current engagement efforts to effectively engage the Latino communities.

The two roundtable convenings allowed for open dialogue between CPW and Latino hunters, providing an opportunity for each to learn more about the other, exchange information about conservation and recruitment efforts on both sides, and discuss how sportsmen and sportswomen from Latino and non-Latino communities can come together to better support conservation.

The Latino Hunter Roundtable provided CPW with several recommendations:

Additional recommendations from the Roundtable are being collated into a toolkit that can be utilized by CPW and other state wildlife agencies to recruit, retain, and reactivate new audiences into hunting and conservation. The toolkit will be presented to state wildlife agencies, at national meetings and made available over the summer and fall.

The TRCP and CPW understand that conservation works best when we work together. To ensure that conservation, hunting, and angling stay relevant to future generations, it is critical that we continue to mentor family, friends, and neighbors in ways that resonate with them. Hunting has long been about community and shared experiences in the field, around a fire, or at the dinner table, and together we will continue to guarantee that all Americans have quality places to hunt and fish.

Top photo by Tim Donovan

As common flood protection structures, earthen levees line American rivers and streams. Levees constructed in response to historic river flooding—where property damage soared and life loss steadily increased—have been relied upon for generations.

But these manmade barriers also work against our natural environment. Connectivity of a river to its floodplain is critical for the exchange of flows with the river, which deposit and transport sediment through the watershed and support the sustainability of fish and wildlife populations. Levee construction across our major river systems has interrupted and prevented this natural and beneficial ecological function of floodplains.

Over time, Congress acknowledged the adverse impacts of human development that depletes habitat by passing the National Environmental Policy Act in 1970 and the Endangered Species Act in 1973, among other legislation. But levees are still used today. Fortunately, there is a way to make communities more resilient from flooding and reconnect habitat that relies on life-giving sediment and river flows.

Numerous levees have performed and continue to perform as they were originally intended. Just ask someone from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. For that matter, just ask me. After 34 years of service with the Corps, I’ve seen the good and the bad associated with levees.

On the one hand, levees have prevented devastating flooding from occurring in large cities and small towns—protecting critical facilities (like hospitals, fire and ambulance stations, utility distribution services, government buildings, and military bases) as well as acres upon acres of productive farmland.

However, many of these levees were designed before we began experiencing the apparent effects of climate change, which could pose higher risks now and in the future.

A levee’s height and width will not change once it has been constructed. No matter how much you water it, that levee will not grow. The design conditions are static, with levee performance being based upon the hydrology and hydraulics from when the levee was originally designed. Unfortunately, the climate is dynamic and, as we have witnessed over the past decade, the intensity and frequency of severe weather is increasing along with the failure of vulnerable levees—most recently within the lower Missouri River Basin.

When a levee fails, the results can be catastrophic to people, buildings, infrastructure, livestock, and cropland. Setting levees back far enough to allow the river more room to convey flood waters, while protecting all landward assets, could solve multiple problems.

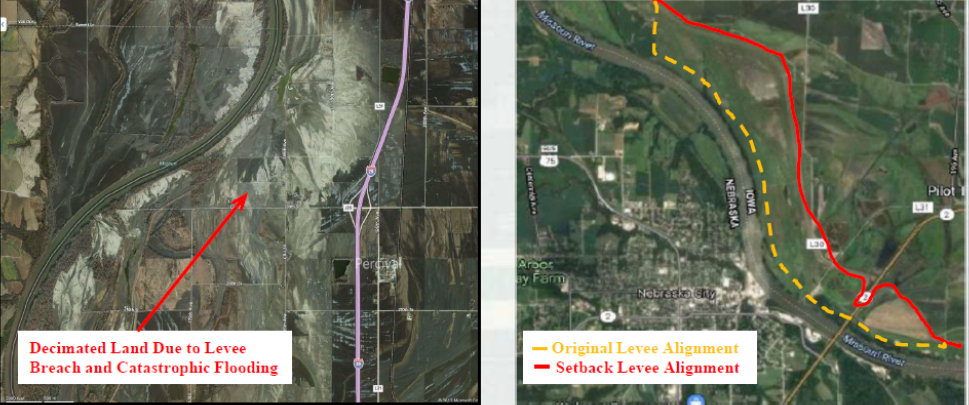

The photo on the left below illustrates the devastation to the land after a levee breach occurred along the Missouri River during the 2011 flood. The photo on the right illustrates the levee setback that was implemented after the flood, improving flood conveyance, reducing the depth of inevitable floods, and increasing the resiliency of the levee.

Further, the land located riverward of the levee has been enrolled into conservation easements, reconnecting a large portion of the historic floodplain and allowing for that critical exchange of flow between the river and the floodplain.

Diversification of flood flows through reconnection of the historic floodplain to the river is the greatest environmental benefit associated with a levee setback like this one. As shown in the images below, fish and wildlife are flourishing within the conservation easements, because they mimic natural ponds and wetlands. The positive trade-off of transitioning some productive cropland to conservation easements by realigning the levee is that fewer levee failures will occur, the setback levee is more resilient to flooding, and the environment has an opportunity to recover.

The cost of setting a levee back from the river can be millions of dollars. The cost of not setting back certain levees, especially those that continue to encounter flood damage, may be costlier in terms of damage to buildings, infrastructure, livestock, cropland, and the environment. While funding from the federal government flows with fewer restrictions to states and local governments after a disaster, it would be beneficial for states and federal agencies to identify vulnerable levees now—prior to flooding.

We must acknowledge that our needs have changed since levees were first designed and constructed. Continuing to rebuild after every damaging flood, rather than implement forward-thinking solutions, like levee setbacks, all but guarantees that fish and wildlife habitat will continue to suffer.

Learn more about this issue and proposed solutions here.

Randall Behm is retired from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers after 34 years as a professional engineer. As a consultant, he now works nationally on the implementation of nonstructural flood mitigation measures and advocates for the setback of perennially damaged levees to improve flood-risk management and environmental benefits.

Top photo by Justin Wilkens on Unsplash

TRCP has partnered with Afuera Coffee Co. to further our commitment to conservation. $4 from each bag is donated to the TRCP, to help continue our efforts of safeguarding critical habitats, productive hunting grounds, and favorite fishing holes for future generations.

Learn More