The future of hunting, fishing, and outdoor recreation businesses will rely on implementing these meaningful water conservation, habitat improvement, and agricultural practices

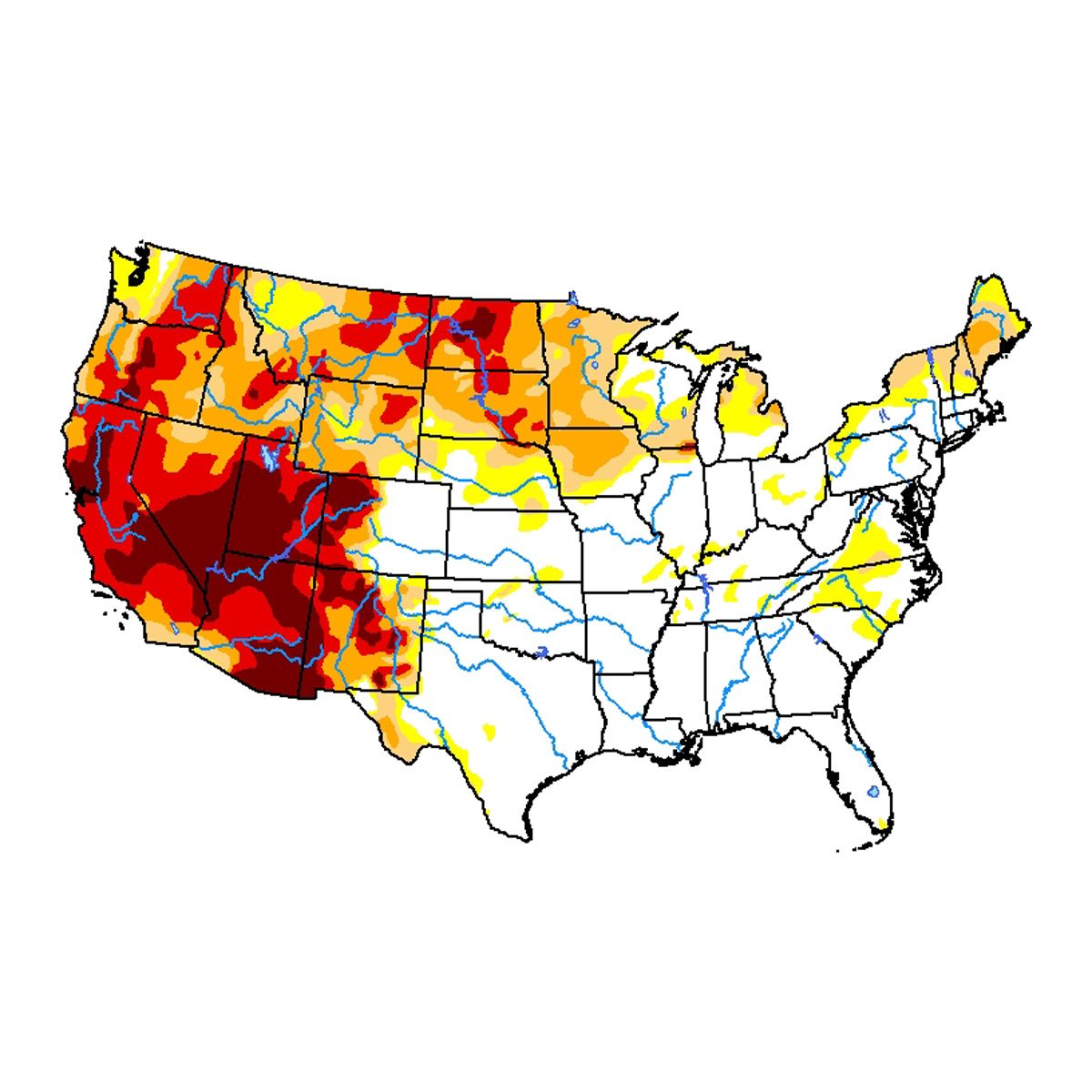

The Colorado River Basin is once again facing scary hot and dry conditions this summer. The current Drought Monitor shows most of the Western U.S. in significant drought, but the Southwest looks the worst:

For the Colorado River Basin, this year is like many since 2002—a period that scientists are now calling the Millennium Drought. About 40 million people rely on this system for drinking water, while most Americans eat vegetables produced in the region’s fields. Many of us also take joyful advantage of hunting, fishing, and other outdoor recreation across the Basin’s vast public lands, including ten national parks.

For all of us, the fact that the Colorado’s large storage reservoirs are only about one-third full is cause for alarm and a reminder that the changing climate has real consequences—for tourism, outdoor recreation businesses, agriculture, and American homes. As a result of agreements reached over the course of the last 15 years, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation will formally make a water shortage declaration later this year that will require substantial reductions in water deliveries, mostly in Arizona.

A new report, Ten Strategies for Climate Resilience in the Colorado River Basin, offers a set of actions that would allow those who live in or rely on the Basin to adapt, reduce pressure on water supplies, and strengthen local economies, all while building climate resilience. These actions, which range from the proven to the emerging and theoretical, would take the Basin well beyond the important water conservation and recycling measures that cities in the Basin have already initiated. And for each strategy, the report identifies potential sources of funding, although significantly more investment will be necessary.

These strategies include:

- Prioritizing forest management and restoration to maintain system functionality and biodiversity

- Restoring highly degraded natural meadow systems to improve local aquifer recharge and water retention, reconnect historic floodplains, and support productive meadows and riparian ecosystems

- Promoting regenerative agriculture—voluntary farming and ranching principles and practices that enrich soils, enhance biodiversity, restore watershed health, and improve overall ecosystem function while boosting local communities

- Upgrading on-farm infrastructure and operations, including water diversion, delivery, and irrigation systems

- Developing cropping alternatives—like shifting to crops that use less water—and market and supply chain interventions to incentivize water conservation

- Incentivizing water conservation and reuse in urban areas by promoting conservation technologies, indoor and outdoor conservation programs, and direct and indirect potable reuse

- Incentivizing modifications and upgrades to reduce water use and increase energy efficiency

- Purchasing or reallocating water rights from closed or retiring coal plants to be used for system or environmental benefits or other uses

- Improving land management practices to reduce the dust on snow effect, which controls the pace of spring snowmelt that feeds the headwaters of the Colorado River

- Implementing solutions to reduce evaporation from reservoirs and conveyance systems

Implementation of these strategies may be challenging and will require change. For example, multiple federal agencies that usually operate in their own silos would have to work together. It will also be important to involve state, local, and tribal governments and to make clear that, when it comes to strategies that may be deployed on private lands, they are voluntary measures—not mandates. Still, taken together, these strategies may help preserve agricultural viability in the Southwest into the future.

Decision-makers will need to weigh the costs, technical feasibility, and political will for moving bold actions like these strategies forward. However, with the president and Congress considering major investments in America’s infrastructure, there can be no better time to secure financial and policy support for these measures.

But we as sportsmen and sportswomen must be engaged in this process. Our ability to advance significant improvements in the management of the Colorado River system thus far is a testament to the power of partnerships. And the hunting, fishing, and conservation community—including the nonprofits behind this report—is prepared to dig in with the Basin’s private landowners, local communities, and government officials at every level to take the next steps. Together, we must adapt the system to a changing climate and build toward long-term climate resilience, while looking out for our fish, wildlife, and economy along the way.

Excellent post! Those of us in the Southwest will be feeling the water squeeze for the foreseeable future and smart land/farm management will help us survive it. Another major factor is the data center boom here in the Phoenix area; they are popping up everywhere, adding serious electric loads and water loads.

The bottom line is, If every one can build what they want and agriculture ls unlimited as well, good luck with having enough water.

Has anyone every thought about pumping water from the Columbia River and sending it South? We have 4.7 miles of fresh water turning into salt. Why?

There are 2 very specific things that would help a bunch. Fallow all golf courses and lawns and remove livestock from our public lands.

No tax payer subsides to entities that do not practice soil and water enhancing actions.

Incentives by municipalities to replace the ever thirsting suburban lawns and public areas with Buffalo Grass would greatly reduce water consumption. The seed is not cheap and it takes patience and persistence to get it established, but the rewards are;

1) NO watering required because it evolved on the short grass prairie and has roots many feet deep. It doesn’t green up until early June but still is attractive in its tan winter hue.

2) More free time – we mow approximately every 3 weeks and it still looks attractive because it only gets about 5″ high.

3) Less wear, noise and pollution from lawn maintenance equipment.

4) It forms a fairly thick mat and propagates from seed and rhizomes so tends to resist invasion by other grasses.

Interesting comments so far and a couple of things caught my eye. First, evaporation with the current uptick in annual average summer temps shows the need for more pipelines instead of canals in irrigation districts. That said, with more money going to infrastructure upgrades from Governments in both Canada and the U.S. That all comes down to politicians having the will to fight for those funds which in the long term will have big improvements in the amount of irrigation farm produce going forward. I think we’ll still need to eat despite climate change!