Here’s how we’d grade the implementation of each private land conservation program included in the last five-year bill—and what can be done better next time

The 2018 Farm Bill seems fated to be remembered as one defined by COVID-19 and the greater political universe. The bill took several steps to regain ground for conservation following agency-wide sequestration, but trade disputes and the onset of a global pandemic changed the reality facing American agricultural producers and strained resources at the USDA, right as implementation of the five-year bill hit its stride.

However, the Natural Resource Conservation Service and Farm Service Agency plowed ahead, with many of the federal employees responsible for Farm Bill conservation programs working from kitchen counters and dining room tables. Two years later, business as usual seems right on the horizon—and so is the next Farm Bill.

To secure the best possible value for hunters, anglers, landowners, and fish and wildlife in the 2023 bill, we need to know what worked and what didn’t. Below is a quick line-by-line report card on the USDA’s implementation of private land conservation programs since passage of the 2018 Farm Bill, plus what we’d like to push for in the next bill.

Voluntary Public Access and Habitat Incentive Program: A+

In March 2020, the USDA awarded $48 million in funding to state and tribal governments from the Voluntary Public Access and Habitat Incentive Program. Later in the year, the TRCP released a report highlighting the innovative ways that states are putting this money to use. States like Michigan, Illinois, and Colorado have used funds to work with landowners to open tens of thousands of huntable acres to the public. Other states have expanded mentorship programs and built websites and mapping tools to make access easier to find. In total, the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies has estimated a return on investment of $5.20 for every $1 in funding to the program.

The swift distribution of VPA-HIP funds and clear benefits should be a sign to the hunting and fishing community to press for further investment in the VPA-HIP when the Farm Bill is reauthorized in 2023.

Conservation Reserve Program: B

Since 2018, the TRCP and our partners have been vocal about the impact that administrative changes had on enrollment in the sporting community’s favorite conservation program: the Conservation Reserve Program. Decisions to eliminate cost-shares and practice incentives and reduce soil rental rates accelerated the CRP’s waning enrollment from 36 million acres in 2007 to 20 million acres in 2020. Fortunately, in 2021, the USDA seized on recommendations from our community to boost enrollment—reinstating incentives and improving the financial reasoning for signing up. Landowners responded, with over 58,000 new contracts and 5.3 million acres enrolled in the program.

There is a General CRP sign-up ongoing through March 11 and a CRP Grasslands sign-up from April 4 to May 13, 2022—so enrollment numbers should continue to climb. But the TRCP and our partners continue to work with USDA officials and lawmakers to identify program improvements ahead of the 2023 Farm Bill.

Environmental Quality Incentives Program: B

Here’s how we arrived at this decent-but-not-stellar grade. First, the positives: EQIP, the most popular working lands conservation program, was significantly expanded in 2018 and has become a central tool in the Biden Administration’s toolkit for addressing agricultural land climate emissions. Increasingly, the NRCS is pursuing innovative ways to draw interest into the most popular working lands program—like a recent announcement that EQIP would offer a Conservation Incentive Contract option, created in 2018, nationwide in 2022. This focuses EQIP practices on specific resource concerns in high-priority conservation areas and provides annual payments over a five-year contract period. These contracts serve to help landowners transition from individual EQIP practices to the whole-farm conservation approach offered by the Conservation Stewardship Program. The agency also recently announced the availability of $38 million for cover cropping demonstration projects in 11 states, advancing the deployment of climate-smart adoption.

The 2018 Farm Bill also expanded eligibility under EQIP programming to water management entities (i.e., irrigation districts) that provide water to farmers and ranchers in the West. Expanded eligibility under EQIP will be a helpful tool in achieving large-scale water efficiency and conservation improvements, which enhance river flows for fish and wildlife. Here’s where things can improve: Based on reports from partners, NRCS state and local staff have received little guidance on how to update EQIP procedures to accommodate new eligible entities and have limited capacity to market the program to eligible users. TRCP is encouraging USDA leadership to provide additional resources to NRCS state and local offices to properly administer and market these new opportunities.

There also continues to be concern in the Colorado River Basin that certain efficiency practices adopted by these entities aren’t translating to water savings benefiting fish and wildlife, despite requirements that efficiency savings not be directed toward activities that increase overall water use. The conservation community continues to work with the NRCS and champions in Congress to ensure that EQIP dollars are achieving the program’s conservation goals.

Climate-Smart Agriculture: A

Among President Biden’s earliest actions in office was an Executive Order directing federal agencies to develop climate mitigation strategies, with a goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. The USDA later released a request for information on how new and existing funding and authorities can be used to encourage the voluntary adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices. This process, which the TRCP and partners took part in, yielded important feedback on the need for everything from improved data quantification and management and the development of climate-smart commodities to better landowner outreach and flexibility. Following the feedback process, the USDA released a 90-day progress report in May 2021.

In February 2022, the agency announced $1 billion for climate-smart commodity pilot projects over a period of five years. The program will support partner-led efforts to bring climate-smart commodities to market, supporting carbon quantification, reporting and verification of climate benefits. These partnership projects will serve as proof-of-concept for the future of climate-smart commodity development. These incentives keep lands from being converted and advance the conservation and restoration of ecosystems like wetlands, grasslands, and forests—all of which is critical to securing huntable habitats for generations to come.

Conservation Compliance: D

In April 2021, the Government Accountability Office released a report detailing ineffective enforcement of Conservation Compliance. Also known as Swampbuster, this accountability effort has been in place since 1985 and prohibits those who drain temporary, seasonal wetlands in the Prairie Pothole Region from taking part in farm bill programs. The watchdog agency found that USDA wetland specialists were only reporting a fraction of the compliance violations they witnessed. Potential violations are only reported if met during an active inspection. So, wetland drainage violations in sight of roads, property lines, and visible in aerial imagery go unreported. In total, the agency reported less than five violations on 417,000 tracts of land between 2014 and 2018.

Since the report was published, the USDA acknowledged failings and agreed to implement a handful of the report’s recommendations. The TRCP, its partners, and greater conservation community continue working to address this decades-old problem.

Regional Conservation Partnership Program: C

As the premier public-private conservation program, the RCPP lends federal resources to locally led conservation projects to carry out conservation on a landscape scale. It was created in the 2014 Farm Bill and expanded in 2018.

In 2021, the NRCS announced $330 million in RCPP funding awards to 85 projects across the U.S. While notable, partner stakeholder groups continue to report that innovative projects, and those with the greatest conservation impacts, often do not move beyond the application stage because of inflexibility in USDA selection criteria. These and other concerns about burdensome contracting authorities are creating an environment where landowners, conservation groups, and private companies hesitate to take part. This must be improved.

Overall Grade for Implementation of the 2018 Farm Bill: B

The USDA and its implementing agencies have the unenviable task of managing the various, and often competing, facets of American agriculture. Particularly in recent years, market fluctuations, global health, and the swing of the political pendulum have all played a role in shaping how farm bill conservation dollars touch the ground. Considering the drawbacks of the 2014 bill, the 2018 Farm Bill remains a significant achievement, and given all that has gone on in the time since, we give the USDA more than a passing grade in its efforts.

In the 18 months between now and expiration of the 2018 bill, the TRCP and our partners will continue to closely track how these important programs touch down on the landscape. In the year ahead, we will begin the process of drafting legislation for inclusion in the bill’s reauthorization. In doing so, we will rely on our dedicated audience of sportsmen and sportswomen to make their voices heard in support of a strong conservation title in 2023.

Check out the TRCP’s Farm Bill resource center to learn more about these important programs.

Top photo courtesy of the USDA via Flickr.

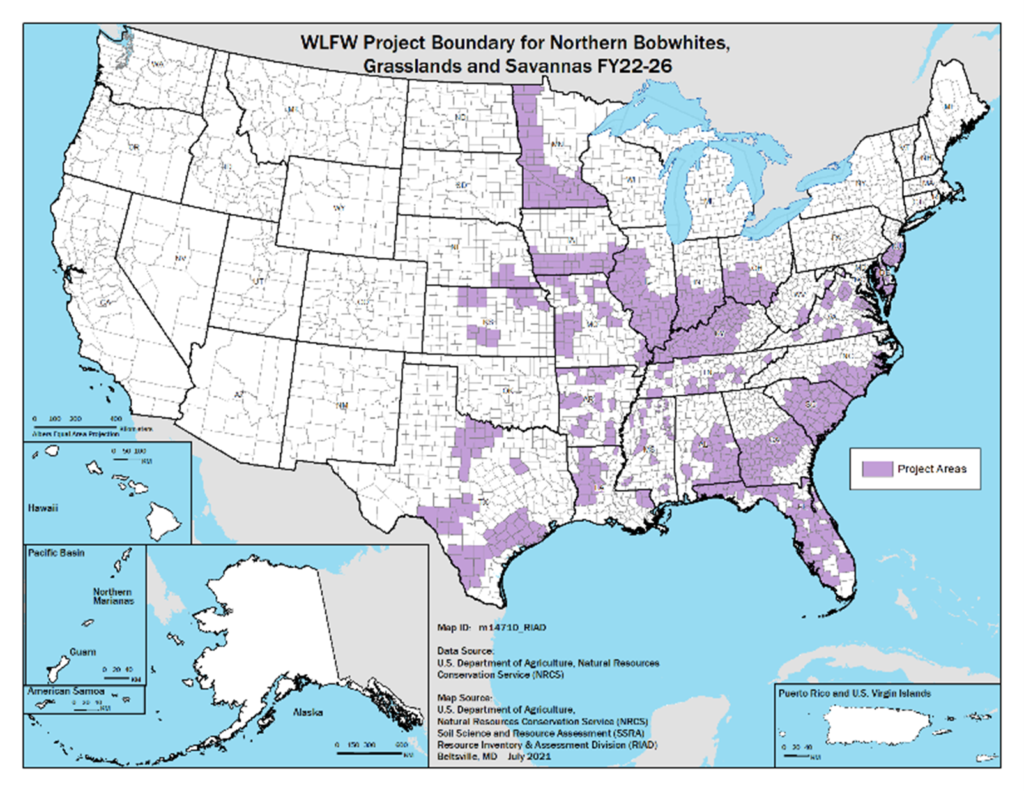

The 2022 framework sets an ambitious course for the future of grassland and quail habitat conservation in the central and eastern U.S.: Through Fiscal Year 2026, the NRCS intends to conserve 7 million acres of bobwhite habitat through the WLFW initiative.

The 2022 framework sets an ambitious course for the future of grassland and quail habitat conservation in the central and eastern U.S.: Through Fiscal Year 2026, the NRCS intends to conserve 7 million acres of bobwhite habitat through the WLFW initiative.

Man I love this I didn’t Bob whites were that widespread. But I love the work you’ll are doing to me there’s nothing more wild sound than the beautiful Bob white call. Takes me back that’s for sure! Get this passed yesterday!!

Very interesting on this, I really enjoyed reading this.

I just learned recently about the bobwhite quail. Would love to learn mor on how to preserve their habitats

Please save their homes n them. Ty!

Growing up in Northern Kentucky, I remember when mowing or having, it wasn’t unusual to jump 2-3 coveys a day. Spent many days afield jump shooting by myself. Haven’t seen a bird on our farms in over 10 years! Would love to stock, improve habitat, or do anything necessary to bring em back.

I hunted them when I was young with my dad. I miss them so much now , just the call that they had. How can I get some on my land now ?

Why not band small land owners and subdivisions together to preserve waterways and creeks from pesticides and natural landscaping plantings to support flora and fauna? What is now on the landscape between the farms connecting natural migration routes and feeding areas? Subdivisions. Why do only large farmers reap benefits and deductions that should be available to group owners?

On 8/13/22 we had a group of 10 in our front yard . Elmer area in Salem co. nj.