A firsthand look at the science that informs smart conservation policy (and allows for powerful, up-close encounters with the West’s iconic big game animals)

Anglers know that there’s a certain magic, when releasing a lively fish, in seeing the flick of its tail propel it back into a “wild” state, as if you’d momentarily held lightning in a bottle. That feeling is magnified many-fold, one might imagine, when letting go of an adult mule deer and watching her trot off toward the horizon on a blue-sky day in sagebrush country.

Needless to say, when faced with the opportunity to do just that by participating in the type of scientific research that informs our work at TRCP, I didn’t have to give it much thought before accepting the invitation. Here’s what I learned from a weekend of capturing and collaring mule deer and bighorn sheep with the University of Wyoming’s Monteith Shop.

(Check out the four-minute feature below and then scroll down to read the story and view additional video shorts from this project.)

One Data Point at a Time

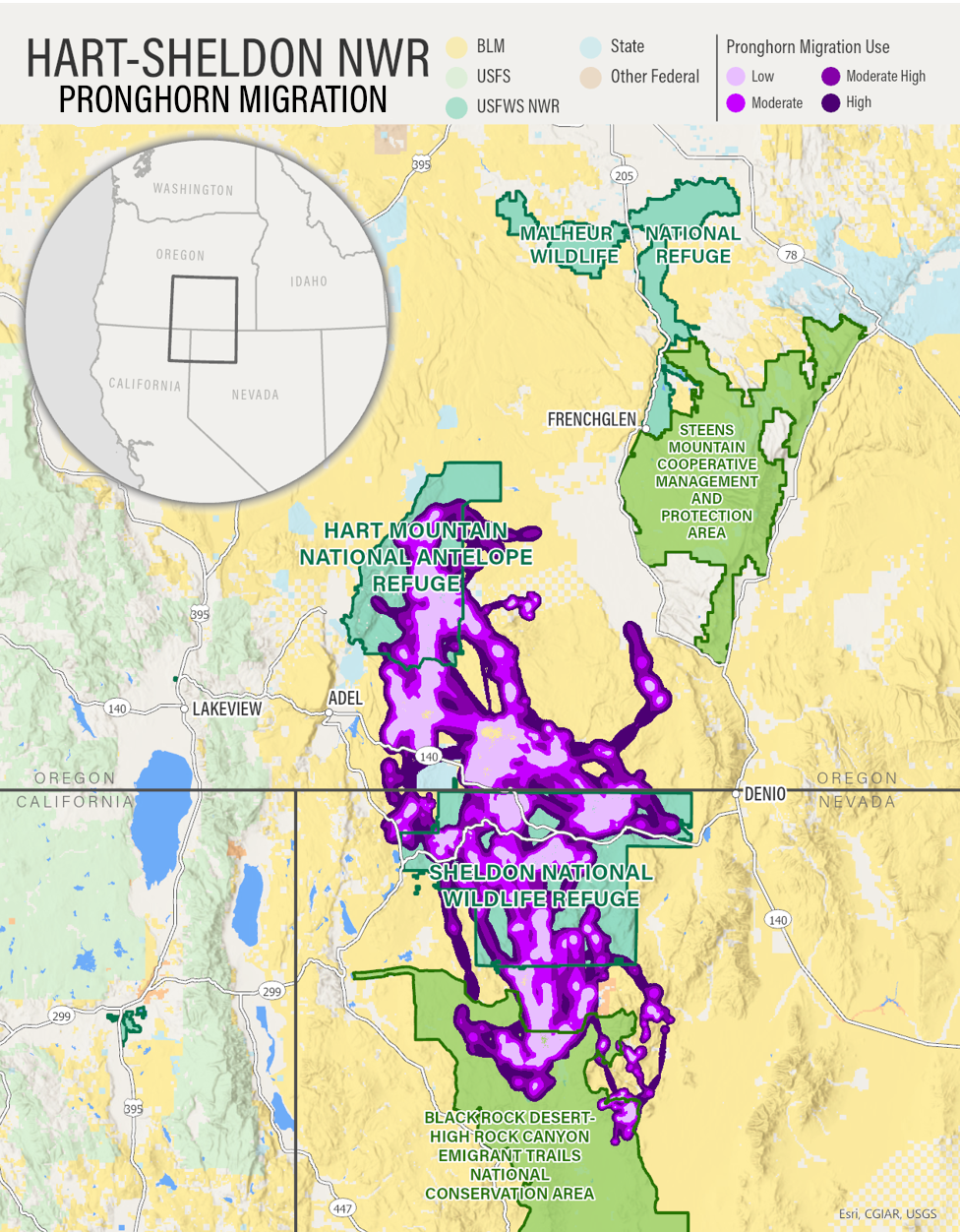

Across the West, there’s no issue to which fresh-from-the-field data is more relevant than the challenge of safeguarding big game migration corridors and seasonal ranges. As development of all kinds sweeps across the Western landscape, transforming and fragmenting habitats at an alarming rate, unprecedented advances in the study of migratory big game animals help inform solutions to ensure these herds can access the food and cover they need throughout the year. And central to our understanding of these issues is on-the-ground, boots-in-the-mud wildlife science.

This is part of the reason I’ve long been intrigued by the work of my friend Kevin Monteith, a professor at the University of Wyoming, and was thrilled to join his team last month for a few days of working with collared bighorn sheep and mule deer.

Kevin’s team—a mixture of Master’s and doctoral students, postdoctoral fellows, and research scientists—had already been in the field for 10 days by the time I met up with them at a Wyoming Department of Game and Fish parking lot in Jackson. Each December and March, the researchers at the Monteith Shop spend three weeks capturing and collecting data from collared big game animals, timing the work to shed light on how winter has affected their physical condition. Then, in mid-May, they capture and collar that year’s offspring, gathering the first of what will be a lifetime of information provided by the study of these animals. On top of those three key periods, various other field work occupies researchers from the Monteith Shop for the rest of the summer and throughout the year.

How It All Adds Up

Some of these different tracking projects have been ongoing since 2013, helping to illuminate the connections between the health and behavior of these animals and the changing landscapes on which they live. The data collected in the field amounts to a highly detailed portrait of these individual animals at a particular moment in time, and when repeated at regular intervals over a long period, it begins to tell the stories of their lives. As the years pass, the data begins to stretch across generations and the collective wealth of information illustrates population-level dynamics.

This is exactly the type of research that tells us, for example, what happens to herd numbers or fawn recruitment in the years following industrial development in a migration corridor or the fragmentation of winter habitat by a new highway.

As sportsmen and sportswomen who care about, observe, and encounter animals like mule deer and elk, it’s easy to take for granted that we know what we do about the bigger picture in terms of what will keep these populations healthy for future generations. To be sure, the most basic pieces of that puzzle are obvious—they need food, water, security, etc. But evidence showing, for example, that a specific change on the landscape will have a particular effect of a certain magnitude on a big game herd allows us to make well-informed, responsible decisions about how to manage our public lands for multiple uses over the long term.

The Main Event

At the day’s outset, a helicopter-based crew, which travels across the country performing this highly specialized work, tracks down the animals using the frequencies emitted by their collars. Individually, these animals are netted, then hobbled and blindfolded, before being transported to Kevin’s team, who set up staging areas in different locations throughout the day to minimize the distance traveled by each animal.

Once they arrive via helicopter, each individual animal undergoes a series of tests. Members of the team weigh each animal and measure their length, girth, and lower leg (metatarsus), while others collect blood, hair, and fecal samples. Portable ultrasound machines allow the researchers to gauge the amount of body fat remaining after a long winter, and to check each animal for pregnancy. For each pregnancy identified, the number of fetuses, as well as the width of their orbital sockets (a key indicator for their stage of development) are noted. The bighorn sheep, which are particularly susceptible to respiratory pneumonia, receive an extra test: nasal and tonsil swabs to test for infection.

Throughout the process, the animals are handled with care and their temperatures are monitored as a way of ensuring that they are not experiencing excessive physiological stress. Each animal also receives a mild pain reliever and fever reducer as a precaution. Behaviors such as vocalizations and kicks observed in the course of the process are all recorded for future reference.

After collecting all of these data, the team checks—and, when needed, replaces—the tracking collars, then marks each animal with livestock paint so that they will not be inadvertently recaptured as the day’s work continues. One finished, we release the deer at each processing site, watching as they spring forth onto the sagebrush-covered landscape, while the sheep are loaded back onto the helicopter to be released where each specific individual had been captured.

The Takeaway

Perhaps the most remarkable part of my experience was watching the Monteith Shop team at work. With every load of animals from the helicopter, they leapt into action unprompted, moving with a care and a seriousness of purpose that never wavered throughout the process. Moments of downtime allowed plenty of laughs and smiles among the group, but a shared sense of responsibility for the welfare of each individual deer and sheep—as well as a shared understanding of each data point’s importance—meant that the whole operation hummed along methodically, efficiently, and deliberately.

I can’t count the number of times I’ve typed the phrase “the latest research tells us,” or some variation thereof, during my tenure with TRCP. That should come as no surprise: Smart conservation policy is grounded in science and derives much of its credibility from dispassionate, empirical data. But even the most objective and matter-of-fact fieldwork does little to dull the wonder of experiencing an up-close interaction with a bighorn sheep or mule deer.

Participating in the hands-on work of the Monteith Shop put into stark relief the strange familiarity, intimacy, and mystery that surrounds each encounter with the West’s big game animals and fuels my fascination with them. In that sense, it was a welcome reminder of why we do what we do at TRCP and instilled in me a greater appreciation for the tireless efforts and dedication of so many others who make our work possible.

Loved this piece. Well-written, informative. Reflects incredibly important work that so well done.