Analysis shows the extent to which recreational trails overlap with important elk habitat in Colorado

Colorado’s resident population and visitor numbers continue to rise, and our year-round presence on recreational trails is impacting elk and other wildlife like never before. When elk are stressed by things like human disturbance, insufficient nutrition, and smaller habitat areas, local populations can struggle and decline.

In Colorado, certain big game herds–including some elk herds—are shrinking, which translates to fewer opportunities for hunters. For the 2022 hunting season, Colorado Parks and Wildlife will issue 1,400 fewer pronghorn licenses, 500 fewer deer licenses, and 800 fewer limited elk tags compared to the 2021 season. The good news is that activities within elk and other big game habitat can be planned and managed to limit impacts when and where it’s needed.

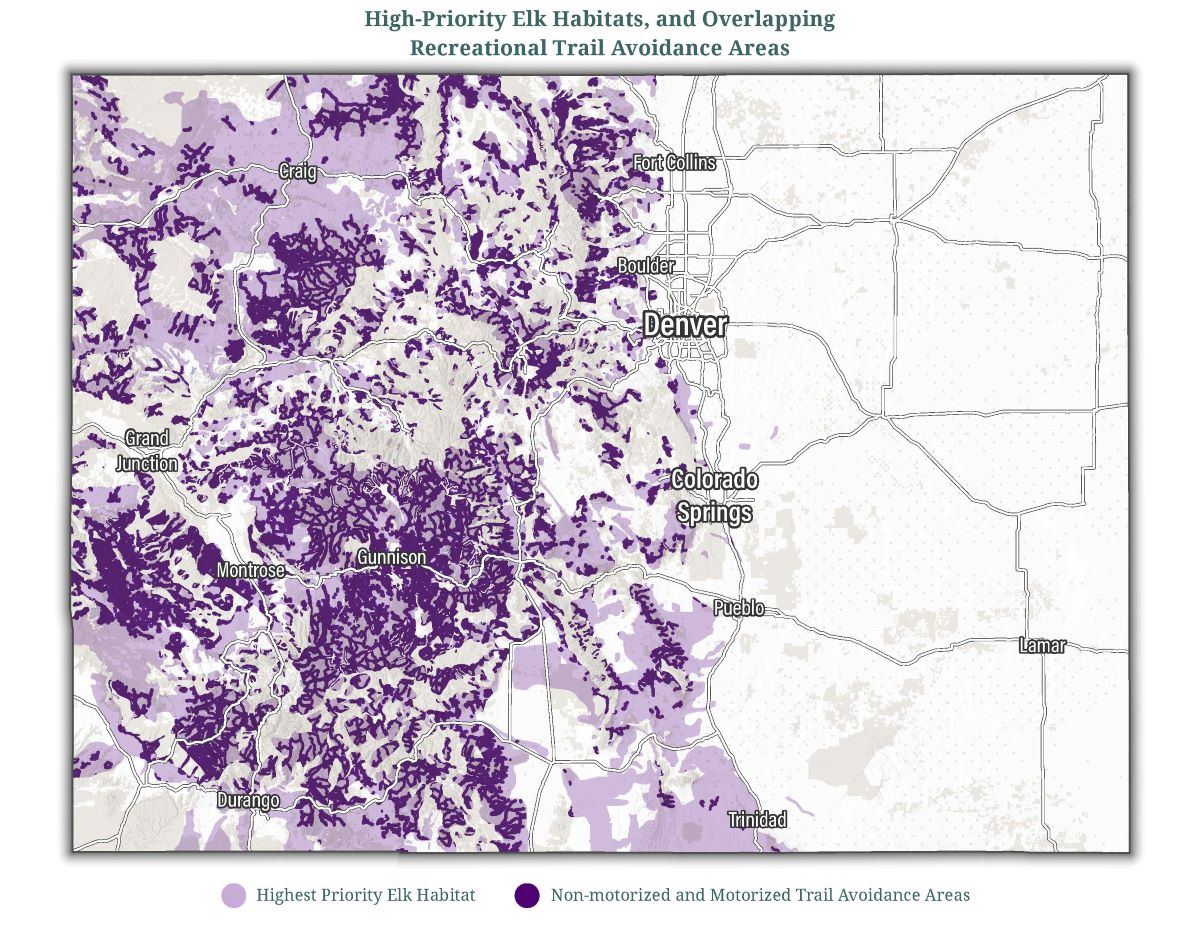

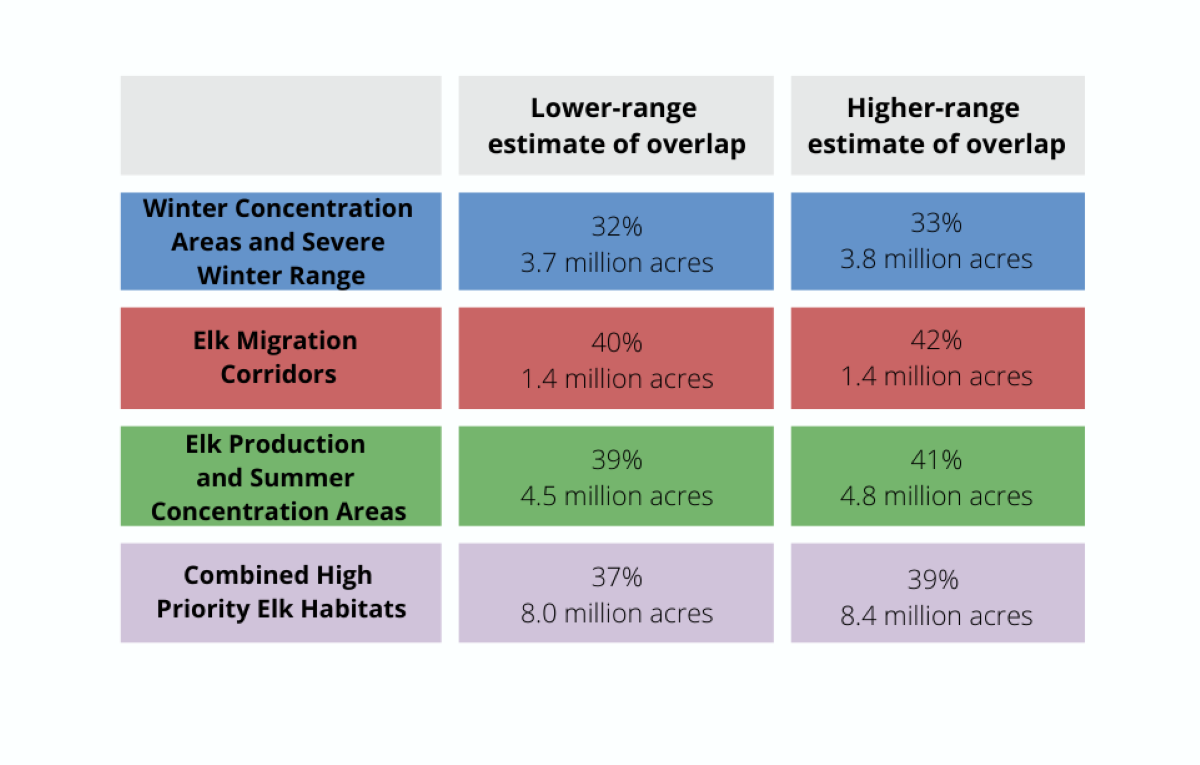

An analysis by the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership shows that around 40 percent of the most important elk habitat in Colorado is already impacted by non-motorized and motorized trail users. In this analysis we look at the overlap between existing recreational trails and high-priority elk habitat.

We undertook this analysis because trail locations and trail use are factors that are known to change elk behavior and their distribution across the landscape, and as passionate elk hunters and active trail users we wanted to better understand our collective trail-based impacts on Colorado’s elk. This statewide analysis provides land managers and partners with an opportunity to visualize where there is already significant overlap between important elk habitats and mapped trail systems, consider where updated management may help prevent changes in elk distribution and declines in local populations, and decide where it may be wise to avoid or limit future trails.

In Colorado, hunting, fishing, and wildlife watching generate $5 billion in economic activity each year, support 40,000 jobs across the state, and enhance our quality of life, but it’s not just hunters who love wildlife. Outdoor recreationists of all kinds value protecting important wildlife habitats and having opportunities to view wildlife, so the need to maintain, conserve, and protect big game habitats and herds is important to the public at-large. When Colorado residents were surveyed in 2014 and 2019, “opportunities to view wildlife” consistently ranked second in the public’s recreation priorities, behind the desire to have local walking trails/paths. Over that time period, the number of days spent using recreational trails had grown 44 percent, while days spent viewing wildlife had increased by 105 percent.

If we want to have it all—strong, diversified recreation economies; enjoyable, sustainable trail systems; and healthy wildlife populations—public land managers will need to minimize impacts to elk and other big game animals by planning trails to avoid high-priority habitat, restricting activity during the times of year when elk are present, and reducing or limiting the trail density within important elk habitats, if time-of-use restrictions aren’t practical.

A Conservation Success Story Under Threat

Colorado has the largest elk herd in the world, and people love seeing, learning about, photographing, and harvesting them. State agencies, federal land managers, and partners worked hard to bring this population up from its low of only 40,000 elk in Colorado in the early 1900s, to around 300,000 today, but some local populations of elk in Colorado are declining once again.

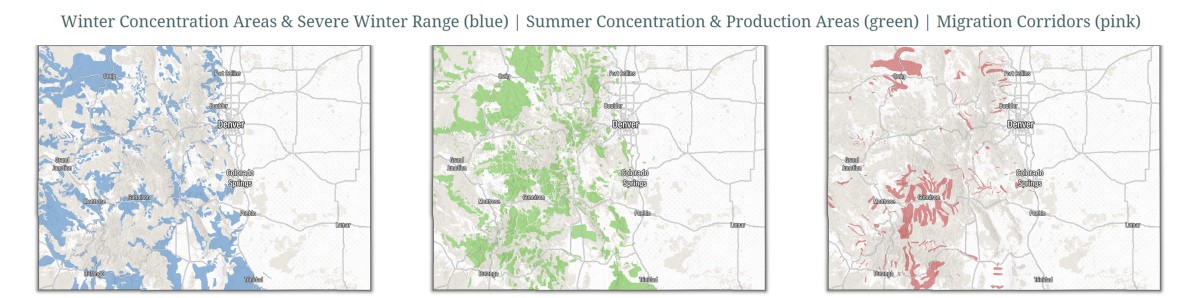

Decades of wildlife research has documented the impacts of road and trail systems and associated human activities on elk behavior and habitat use. Throughout the year, elk need resting areas, food, water, and the ability to move freely between seasonal habitats to access high-quality forage and other essential resources. Within their overall range, elk migrate to different kinds of habitat throughout the year. Elk generally spend winters at lower elevations, where there’s less snow, then move higher into the mountains in the spring and summer in search of cooler temperatures.

Elk also pass down the knowledge of migration patterns to their offspring. In this way, many seasonal habitats, migration routes, and stopover areas are multigenerational—some are even thousands of years old. When new trails bisect well-established migration routes, or if trails in elk seasonal habitat become busy all year round, it can inhibit elk use of these habitats and negatively affect the herds’ ability to successfully raise offspring, which can over time lead to a declining local population.

Elk can survive in some of our state’s harshest environments, but the research shows that additional disturbance from humans during their toughest times of the year can prove fatal. In a study of the elk herd in Vail, Colorado, researchers found that if cow elk had to move in response to hikers an average of seven times during calving, about 30 percent of their calves died. Resulting data models suggest that if mother elk were disturbed 10 times during calving, all of their calves would die. When researchers stopped sending hikers through calving areas, the calf survival rate recovered. This suggests that limiting disturbance in production areas and summer concentration areas during calving season could help increase elk calf survival rates.

Our Analysis

We used a 2018 study on elk response to trail-based recreation that documented elk avoidance of areas around trails and at what distances, depending on the type of use.

Elk stayed about 547 meters away from hikers; 662 meters away from mountain bike riders; and 879 meters away from ATV riders. Using these avoidance distances, we estimated how much of the highest priority elk habitat on either side of existing trails may be rendered unusable for elk as a consequence of high-frequency trail use. While elk overall range covers a majority of the state, the habitats we used in this analysis cover about one-third of the state and include winter concentration areas, severe winter range, migration corridors, production areas, and summer concentration areas. Because these habitats are particularly important to the elk life cycle and overall population stability, we refer to them in this analysis as high- or highest-priority habitats.

The lower-range estimates for overlap between trail avoidance areas and elk habitats use the hiker avoidance distance along non-motorized trails (547m) and the ATV avoidance distance (879m) along motorized trails.

The higher-range estimates for overlap between trail avoidance areas and elk habitats use the mountain biker avoidance distance (662m) along non-motorized trails and the ATV-avoidance distance (879m) along motorized trails.

The Path Forward

As is, nearly 40 percent of the highest-priority elk habitat in Colorado is at risk of being effectively abandoned by elk due to recreational trails and trail use. It’s imperative that Colorado residents, tourists, and land managers recognize that all land uses can negatively impact the elk and wildlife habitats that are so highly valued by us all. This is why the TRCP is calling for hunters, outdoor recreationists, and local, state, and federal agencies to commit to smart recreation planning and maintaining and conserving functional, intact elk habitats—while we still have them.

Land managers at all levels must be intentional when planning new recreational trails, avoiding the highest-priority habitats altogether or minimizing anticipated impacts by planning for enforceable seasonal closures and lower route density. The recommended management actions described in Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s 2021 Guide to Planning Trails with Wildlife in Mind are meant to avoid and minimize impacts to big game from new trails (Appendix A, pp 44-45) and are consistent with CPW’s recently updated and well-vetted recommendations for its defined high-priority habitats. As other states across the country experience increases in recreation development, this information may serve as a helpful resource in efforts to plan more wisely.

These recommendations specify a density limit of one linear mile per square mile route for motorized and non-motorized roads and trails in migration corridors and other high-priority big game habitats. This helps ensure that important big game habitats are easy for animals to pass through—or “permeable”—and that they remain connected and usable. Conserving different parts of important elk habitat through strategic, science-based management, as well as public education, can increase population stability and resiliency by enabling elk to find the kind of forage, water, and cover they need throughout their lifecycle.

Local, state, and federal agencies are increasingly utilizing the latest data and science on big game animals to guide their recreation development and management decisions, and it’s an important time to make sure more stakeholders are aware of opportunities for better planning and management.

The Colorado Bureau of Land Management intends to incorporate the latest science into Resource Management Plans across the state to maintain, conserve, and protect big game habitat. We encourage the BLM to utilize this science to support responsible recreation planning and management so that Coloradoans can have it all: strong recreation economies, world-class big game populations, and exceptional outdoor recreation opportunities.

Take action using our simple advocacy tool to send this message to the BLM: Colorado BLM can be a leader in responsible recreation management and conservation of big game habitats through the Big Game Corridors RMPA.

TAKE ACTION HERE

Photo by Jasper Nance via Flickr

Great analysis and thank you for standing up for our native elk and the habitat for many other wildlife species. What is even more concerning is that there are just as many illegally constructed trails in Colorado as there are authorized system trails so your estimate of elk range impacted is a minimum estimate. Most illegally constructed trails are not mapped other than on certain mobile phone apps like Strava, Alltrails, etc. Public land managers must take action to manage illegal trail construction as well as authorized trail systems if our wildlife habitats and the species it supports are to remain viable.

Thank you so much, Janet! We certainly agree.