Now is our best, and maybe our last, chance to act on behalf of this iconic, American bird

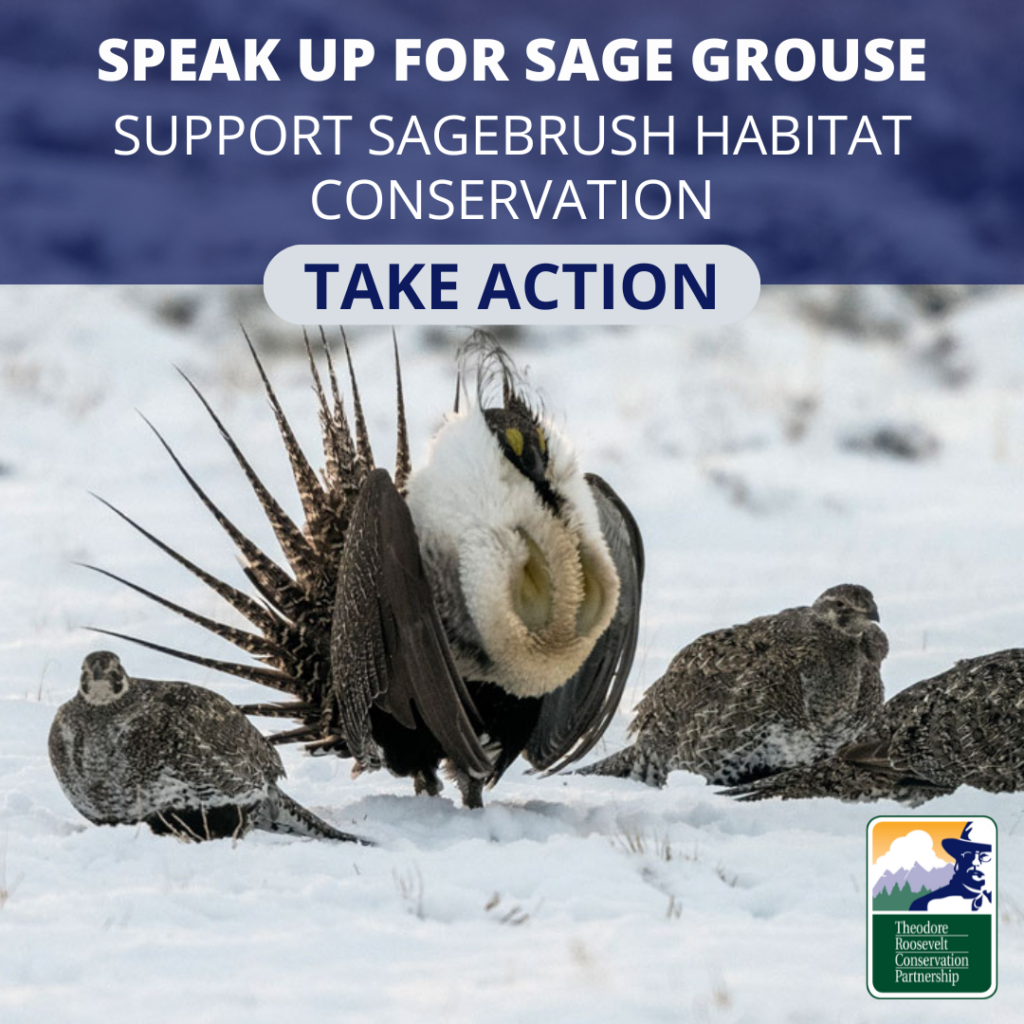

Each spring across the vast, but increasingly fragmented, sagebrush ecosystem, greater sage-grouse perform their ancient and elaborate mating ritual with fewer and fewer performers. As an aging biologist, I’ve been witness to the drama of the display, the loss of the bird and its habitat, as well as unprecedented efforts to conserve both.

At his 2007 Sage Grouse Summit in Casper, Wyoming, Governor Dave Freudenthal didn’t mince words, “The scientific picture is clear,” he said. “We need to roll up our sleeves and develop a plan to protect and restore core sage grouse habitat. We have a narrow window of opportunity to protect the grouse and prevent it from being listed as an endangered species.”

That statement catalyzed policy-making efforts in Wyoming, often mirrored in other states, which were then largely incorporated into range-wide plans approved by the BLM and USFS in 2015. Cumulatively, these plans—shaped with collaboration from Wyoming’s industries, non-governmental organizations, and government agencies—provided the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service with the basis to determine that the greater sage-grouse was not warranted for listing under the Endangered Species Act. Unfortunately, the plans developed in 2015 were never fully implemented.

Our success or failure with greater sage-grouse will be measured by whether or not we maintain enough of the remaining sagebrush sea so that the primal, guttural sounds of strutting sage-grouse continue to punctuate the clear, cold air of spring sunrises across the West.

My 33-year career with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, the last 15 years of which were as the state’s sage-grouse coordinator, meant I spent thousands of hours out in the sagebrush. Over those decades, I learned that this conservation effort, and the threats to this ecosystem, is about much more than just a single species. The problems associated with a breakdown in the health of sagebrush country resulting from massive wildfires, invasive plants like cheatgrass, woody species expansion, and human infrastructure and disturbance impacts all of us, here in Wyoming and across the West. These lands underpin the economies of our rural communities.

In an unsettling revelation, we’ve recently learned through satellite imagery that the West is losing 1.3 million acres of functioning sagebrush habitat every year. And because the bird depends on healthy sagebrush habitat, the range-wide population of sage-grouse has declined 80 percent since 1965 and half of that decline has happened since 2002.

But we now have an opportunity to realize a healthier future for this ecosystem. The BLM, which oversees 67 million acres of sage-grouse habitat across 10 states, is currently updating the prior plans using new science and input from its partners.

Again, the health of the sagebrush ecosystem is larger than just one species. Our collaborative conservation efforts must shift from a sage-grouse focus to a sagebrush biome focus in order to more effectively address the threats facing not only sage-grouse but the entire ecosystem and those species, including human users, reliant on it. I implore the BLM to better incorporate this concept into their decision document.

Also, any and all plans, including those of the states, must make a commitment to transparency and collaboration in managing the sage-grouse habitat. Open data sharing across administrative boundaries is essential in fostering an inclusive environment where scientists, policy makers, and the public can access and contribute to the ecological data that guides management decisions. This approach not only enhances the trust and cooperation among stakeholders but also strengthens the scientific basis for those decisions and provides defensible evidence of the successes and failures of management actions.

Here in Wyoming, we are lucky to still have some relatively intact landscapes that rise above others in terms of their value to sage-grouse and associated species. I support efforts to secure the most effective safeguards for these “best of the best” areas, which are resistant to impacts like invasive species and resilient in their ability to return to good habitat after an impact such as wildfire. These landscapes are the cornerstones upon which the survival of the sage-grouse depends. Irreplaceable places, such as the Golden Triangle in western Wyoming, have such high biological value that these habitats must receive the highest level of conservation.

The current proposal by the BLM to update its sage-grouse management plans is an important step forward. By focusing on strategic habitat management, implementing open data practices, and utilizing advanced adaptive management tools, we can forge a sustainable path for the sage-grouse. This approach will not only benefit the bird but also the myriad other species and human communities that rely on a healthy sagebrush ecosystem. It’s a chance to reaffirm our commitment to conserving a vital part of our natural heritage thereby ensuring that we hand these natural resources in good condition to future generations.

Historically our record is less than stellar when it comes to grouse conservation. The heath hen of the eastern coastal barrens is extinct. The highly endangered Attwater’s prairie chicken is hanging on by a thread along the Texas Gulf Coast. And lesser prairie chicken populations in the southern Great Plains are now listed as threatened or endangered. Our success or failure with greater sage-grouse will be measured by whether or not we maintain enough of the remaining sagebrush sea so that the primal, guttural sounds of strutting sage-grouse continue to punctuate the clear, cold air of spring sunrises across the West.

Tom Christiansen retired after a 33-year career with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department where he served as a regional wildlife biologist and then as the statewide sage-grouse program coordinator. Tom served on the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ Sage and Columbian Sharp-tailed Grouse Technical Committee, the Rangewide Interagency Sage-Grouse Conservation Team, and the Wildfire and Invasive Species Working Group. Like sagebrush, Tom’s roots run deep in Wyoming. His family has maintained continuous residence in Wyoming since 1885.

A version of this article was published by the Casper Star Tribune.

Photo credit: USFWS

Much of the Attwater prairie chicken decline can be laid at the feet of bankers, big corporations, and especially land developers.