Support sustainable native fisheries by targeting, removing, and cooking up these four delicious, invasive fish species

Many aquatic invasive species (AIS) are causing harm to American fisheries and affecting recreational fishing, from flora like hydrilla and hyacinth to fauna like zebra mussels and Asian carp. For this reason, TRCP and its partners convened an AIS commission in 2022. But not all AIS issues can be targeted by anglers, and fewer still are good to eat. We narrowed the list to TRCP’s top four AIS species for anglers because they are fun to catch and good to eat, and our fisheries benefit when we remove them.

If you decide to pursue any of these fish, search for the competitions set up to incentivize their removals. And even if you elect not to eat them, if you ever catch them in locations where they are considered problematic and are not protected, remember that it’s best to not return them to the water.

Northern Snakehead

Take some regular old freshwater fish and Frankenstein it – giving it the head and elongated body of a serpent, the teeth of a wolf, and the abilities to wriggle over land and survive out of water for more than a day – and you have yourself a northern snakehead. Native to China, Russia, and the Korean Peninsula, these bizarre, air-breathing fish probably became established in the U.S. after aquarium owners and others intentionally released unwanted specimens into local waterways. These aggressive top predators can outcompete native fish for food, with adults consuming smaller fish, crustaceans, reptiles, amphibians, and even some birds. Anglers prize them for their explosive strikes and delicious filets. While now established in the Mid-Atlantic and Chesapeake Bay regions, as well as in Arkansas (and recently spreading from there to the Mississippi River), they’ve also been detected in other states like California, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, and North Carolina, but have no established populations there.

- Size: Typically, mature specimens are in the 18- to 30-inch range, but can reach over 3 ft. in length and more than 20 lbs.

- Where to Target: The Potomac River drainage and other portions of Virginia and Washington, D.C., as well as in Maryland; Arkansas, New York, and Pennsylvania also offer limited opportunities

- How to Catch: Focus on slow-moving or stagnant freshwater streams, rivers, or ponds with aquatic vegetation present, and fish for them as you would for largemouth and smallmouth bass, using spinners, frogs, buzzbaits, bladed jigs, and topwater lures; bowfishing can also be used to harvest these fish

- Best Times: Early April through early October; live bait can also be used for fishing during cooler fall and winter periods

- How to Prepare: The snakehead’s mild, flaky-but-firm, low-fat flesh is versatile and ideal for pan-searing, grilling, frying, smoking, or stews, with little seasoning required; just be sure to remove the skin before cooking

Blue Catfish

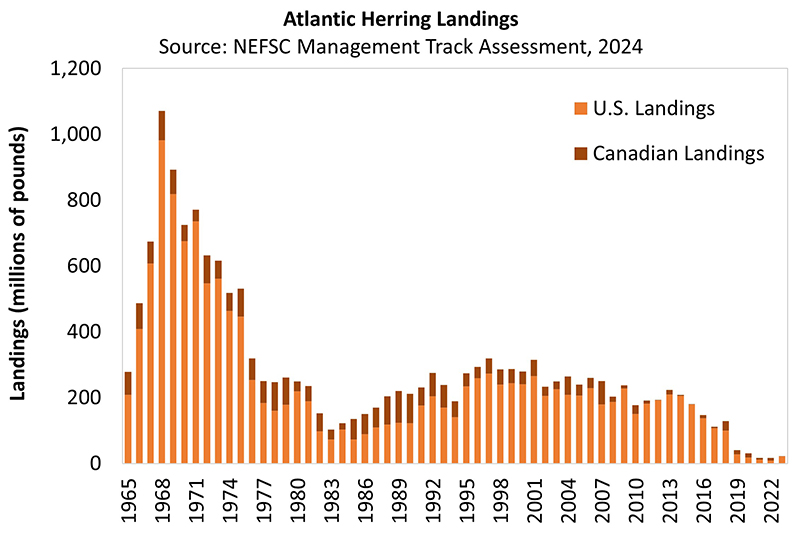

While a native species in the Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, and Rio Grande river basins, blue catfish were introduced in the Chesapeake Bay area in the 1970s. As an apex predator that can thrive even in brackish waters and grow to more than 100 pounds, their population eventually exploded and they are now wreaking havoc on local ecosystems by eating a wide range of important native species in the Bay region, including menhaden, herring, striped bass, and blue crabs. Blue catfish can be found even far up Nanticoke River tributaries in Delaware, and are present in many Southeastern states, where they are considered more naturalized and populations have not exploded like they have in the Mid-Atlantic. Even if blue cats are native where you live, they’re still worth targeting for their sheer potential size and deliciously mild, firm flesh. There’s so good to eat, in fact, that a commercial industry now targets them in the Chesapeake Bay region to supply local restaurants and markets.

- Size: Up to more than 6 feet and 100+ lbs.; avoid eating fish over 30″ long

- Where to Target: Freshwater and brackish Chesapeake Bay river systems and tributaries in Maryland, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and Delaware; click the state links to see fish consumption advisories to avoid eating these and other fish from areas with high contaminant levels in the water

- How to Catch: Blue cats will eat anything, are fairly easy to catch, and a good choice for targeting with kids or inexperienced anglers, fishing near the bottom using fresh cut baits like shrimp, chicken liver, or fish, or live bait for larger catfish; trot lines can also be used if the goal is simply to catch as many fish as possible

- Best Times: Can be fished year-round, with the spring months being particularly good; in the winter they are biting when not much else is, mainly in the warmer daytime periods; nighttime and low-light conditions are best in warmer summer months, and give anglers quarry to pursue to give striped bass a breather

- How to Prepare: Blackened, pan-seared, deep fried, broiled or grilled (catfish filets hold up remarkably well on a grill); be sure to remove the skin before cooking

Lionfish

An attractive, audacious, and venomous marine species native to Indo-Pacific coral reefs, lionfish were first detected in U.S. waters off Florida roughly 40 years ago. It’s thought that people also inexplicably have released them from home aquariums into the Atlantic Ocean multiple times since. (A good reminder that people should never release any pets into the wild!) They have now unfortunately spread throughout the Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean from New England to Texas and the Bahamas to the Greater Antilles. Their heaviest concentrations are in Florida, the Keys, and most Caribbean islands, with detections even having occurred in the saltwater portions of the Everglades – as if South Florida and the Everglades didn’t have enough invasive species problems to deal with already. Lionfish have become a serious problem because they gorge on dozens of species of juvenile reef fish that would ultimately grow to be bigger fish we like to catch. They can eat prey more than half their own length; have no real predators in the Western Hemisphere; and compete for food with important sportfish like snapper and grouper. Despite having venomous spines (which are painful, but not deadly), the flesh is perfectly safe to eat.

- Size: Up to 15 inches or more and about 2.5 lbs.

- Where to Target: Artificial or natural reefs and structure (the deeper, the better) off Florida and Alabama; internationally, in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Bahamas

- How to Catch: Spearfishing (pole spears or Hawaiian slings) using scuba or snorkeling gear; they are surprisingly easy to harvest, due to a lack of predators that makes them unlikely to evade pursuit

- Best Times: Any time of year, ideally near dawn and dusk

- How to Prepare: They are in the same family as Pacific Coast rockfish, which are prized for their meat; their mild, buttery filets have been compared to grouper or mahi-mahi

Yellowstone Lake Trout

Though most coveted trout species are actually considered invasive in at least parts of the U.S., they have long been established and often support economically important fisheries. However, some trout species in some areas are considered more destructive than valuable, so fisheries managers are working to eradicate them. The Yellowstone National Park region is home to non-native rainbows, browns, and brookies, but it’s the lake trout that are a problem. Both lake trout and native cutthroat trout are found in Yellowstone Lake, the largest high-elevation lake in North America, with lake trout both preying on and competing with cutthroats. A single lake trout can eat dozens of cutthroat trout every year, and this loss of the native fish is contributing to declines in many other wildlife species. In Yellowstone Lake, park regulations actually require anglers to keep or at least dispatch all lake trout they land. Added good news is that you’ll probably also be able to catch (and release) some big cutthroats when you’re out there.

- Size: Around 20 inches typically, but up to 36 inches and nearly 40 pounds in this region

- Where to Target: Yellowstone Lake, WY; noted spots include Carrington Island by boat or shore fishing in the Bridge Bay and West Thumb areas

- How to Catch: Fly fishing by stripping a streamer with a baitfish pattern, or gear angling using deep-diving lures or vertical jigging in deeper water; guided fishing tours and boat rentals are available

- Best Times: Legal in the park from Memorial Day weekend until early November, but fall is the best time, when lake trout move into the shallows to spawn

- How to Prepare: High in healthy omega-3 fatty acids, they can be pan-fried or baked; they also cook nicely over an open fire in a grill basket (bring some butter and lemons)

What We’re Doing About AIS

TRCP recently worked with Yamaha Rightwaters, YETI, the American Sportfishing Association, Bass Pro Shops, and other partners on an AIS commission to address the need for better prevention and mitigation of aquatic invasive species. The commission’s final recommendations, finalized in 2023, included the need to modernize federal law and policy, increase targeted funding, maintain fishing access, and increase public education. See the full Aquatic Invasive Species Commission report here.

A special thanks to Noah Bressman, an assistant professor and AIS expert at Salisbury University, for helping confirm information for this blog, and for providing the snakehead photo in the banner image.