IMG_3206

Do you have any thoughts on this post?

We don’t make bigger investments in conservation than those in the Farm Bill. Totaling about $6 billion per year it is the single largest investment in conservation that the federal government makes on an annual basis.

Every five years, Congress drafts a new Farm Bill. It’s a massive piece of legislation that supports agricultural producers and ensures hungry families have food on their table. Tucked inside this legislation are crucial conservation programs that incentivize habitat creation, sustainable agriculture, and even access to private land for hunting and fishing. The reauthorization and improvement of these programs is a top priority, not just within the TRCP, but for our partners and the agriculture and nutrition communities.

The 2018 Farm Bill expired on September 30, 2023, and was eventually extended until September 30, 2024. Early this summer, there was a flurry of activity in the Agriculture Committees. Unfortunately, budget challenges and policy differences have so far prevented the consensus needed to pass any bill in a split Congress, and especially one that traditionally generates wide bipartisan, bicameral support.

Are we in new territory? What is, and what isn’t at stake for hunters and anglers? Here are six things you need to know:

Reauthorizing and updating Farm Bill programs is always important (I don’t think anyone would argue with me when I say the world is a different place than it was in 2018). But for hunters and anglers, and really anyone who cares about a sustainable food system, there is a major incentive to passing a Farm Bill now. The budget reconciliation bill, commonly known as the Inflation Reduction Act or IRA, included nearly $20 billion for climate-smart uses of Farm Bill conservation programs. Currently, all “Four Corners” of the Ag Committee (the Chair and Ranking Members of both the House and Senate Committees) are calling for the remainder of those funds to be incorporated into the Farm Bill baseline and used for conservation. The process for this is complicated, but the important part is that doing so would raise funding for Farm Bill conservation programs by nearly 25%. If Congress fails to act this year, that number will decrease considerably next year and beyond.

“Every day – or year – that goes by without a new Farm Bill, our nation’s ability to conserve habitat and increase sportsmen’s access through CRP and VPA-HIP will suffer. Right now, our opportunity to prioritize agriculture and conservation is greater than ever, as is the risk of letting partisan politics prevent us from supporting our farmers, ranchers, and private landowners with the tools and resources they need to put conservation on the ground.”

Andrew Schmidt, Director of Government Affairs for Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever

Although the challenges this Farm Bill is facing feel daunting, there is plenty of precedence for a delay. Congress is often late in passing Farm Bills. The longest recent process was for the Farm Bill that was signed in 2014 – discussions began in 2011, and it should have been reauthorized in 2012. Both the 2008 and 2018 Farm Bills were several months late as well.

This history of challenges may indicate that passing Farm Bills is getting more difficult, but it also demonstrates that while coalition efforts toward highly bipartisan bills might be slow, they are effective.

In addition to providing supplemental funding, the Inflation Reduction Act reauthorized several conservation programs through 2031.

Even if a new Farm Bill or an extension isn’t passed, many practices that benefit hunters and anglers will continue through the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP), and Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP). Through these programs, wetlands will still be restored and protected, upland habitat will still be managed, and field buffers will still be planted to improve water quality.

Not all of the programs we care about have been spared. The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) has expired. It is one of our country’s most successful conservation programs and provides tremendous benefits for wildlife and habitat. Existing contracts will continue, but new acres can’t be enrolled. This means that the CRP will slowly, but steadily, shrink until either a new Farm Bill is passed, or the current bill is extended. This can lead to a loss of habitat for countless species across the country. Luckily, relatively few contracts are set to expire in the upcoming months, so the overall picture is a little less bleak.

Another key program for hunters and anglers, the Voluntary Public Access and Habitat Incentive Program (VPA-HIP), also suffers from a delayed bill. Funding for VPA-HIP, a crucial Farm Bill program that has opened hundreds of thousands of private acres for walk-in access to hunting and fishing, has historically been distributed once per Farm Bill cycle. VPA-HIP received $10 million when the Farm Bill was extended last year, but without a new Farm Bill private land access programs across the nation will suffer from a lack of much-needed resources.

“The Farm Bill impacts all Americans by investing in conservation and natural resources. Its conservation programs drive beneficial practices across the country—creating wildlife habitat, improving water quality, repairing soil health and protecting human health. Our lawmakers have an opportunity to make a generational investment in these programs and lay a foundation for a more resilient future. But they must get the timing right to maximize their impact. Congress should seize the opportunity to protect our natural resources by passing a bipartisan Farm Bill this year.”

Kate Hansen, Agriculture Program Director for the Izaak Walton League of America

The next few months will be critical for the Farm Bill and the conservation programs we cherish as hunters and anglers. Congress is out of session until after the November 5th election, so we won’t see action before then, and any post-election progress will compete with the appropriations process for lawmakers’ time. Passing a Farm Bill on such a short timeframe will be an uphill battle, but we will keep the pressure on Congress to get this bill passed and avoid a missed opportunity to fund conservation, and we will work to ensure that hunter and angler priorities are met.

In the face of gridlock, conservation is, and should be, a shared priority regardless of party affiliation or ideology. Congress needs to hear that this is important to you. Take action here and stay up to date at trcp.org/farm-bill.

Louisiana’s extensive barrier islands are among the many features that distinguish the state from its Gulf of Mexico neighbors, as well as every other Atlantic Basin state.

Certainly, others have barrier islands and extensive beach shorelines. However, none of them have the unique and numerous mix of headlands and back-barrier marshes of the Bayou State, thanks to the shifting deltas and fertility of the Mississippi River.

While the brown river silt and thick, sometimes rotten-smelling mud isn’t the tourist attraction of white sand and high-rise hotels, the fish, crabs and, especially, native and migrating birds sure do love those “ugly” beaches and marshes.

Singling out one barrier island or even a chain of barrier islands as most important or most unique is difficult. They all serve multiple purposes as vital habitat for fish and birds (and fishermen and bird watchers) and all play a crucial role in knocking down storm surge and protecting more sensitive inland wetlands and communities from bearing the brunt of the strongest hurricane waves. The Chandeleur Islands, though, stand out.

The Chandeleurs are home to the northern Gulf of Mexico’s largest seagrass bed, encompassing more than 5,000 acres and providing food and shelter for innumerable fish, mammals, sea turtles, and birds.

It may come as a shock to most Louisiana waterfowlers that tens of thousands of diving ducks, particularly redheads, spend part of their winter on northern Chandeleur’s massive grass flats. An estimated 40,000-50,000 birds utilize the islands each winter and more than 30,000 sea birds make their nests on the islands annually.

The islands’ remote nature has left them unmolested, but also passed up for large-scale restoration projects.

Those flats also attract sea turtles, most notably endangered Kemp’s ridley turtles. Biologists believed for decades Kemp’s ridleys, while ranging Gulf-wide and along the Atlantic Coast, only nested in Mexico and South Texas. Not so, according to a host of recent findings by Louisiana’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries and Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) that show dozens of nesting sites along the Chandeleur’s beaches.

Of course, Louisiana anglers and saltwater fishing enthusiasts world-wide know the Chandeleurs for their massive schools of redfish, extraordinary speckled trout production, enormous populations of sharks, and even as a stopping and feeding spot for migrating tarpon coming from Florida each summer to feast on pogies and mullet near the Mississippi’s mouth.

This remarkable bounty of fish and wildlife prompted President Theodore Roosevelt to designate the islands as the Breton National Wildlife Refuge in 1904, the second-ever National Wildlife Refuge established in the United States.

There’s no such thing as an easy trip to northern Chandeleur Island. It’s more than 30 miles across a lot of open water from any launching spot along the Mississippi coast. Add a dozen or more miles to that from popular Louisiana ports.

Its remote nature has left the islands mostly unmolested by people and keeps predators like foxes, racoons, and other egg eaters away from bird and turtle nests. But, because the islands are so far away from the mainland, it also meant they were often passed up for large-scale restoration projects.

The storm surge reduction benefits just didn’t score as highly as islands in the Barataria or Terrebonne basins, while the distance from shore meant additional expenses in moving material and manpower on site. Facing limited budgets, state coastal planners had to pick islands that had the most combined benefits for both people and animals.

Construction could begin in 2026 to restore more than 13 miles of the barrier island chain.

Ironically, it’s the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil disaster that changed the equation for the Chandeleurs. The impacts to sea turtles, birds, fish, and other wildlife across the northern Gulf means habitat restoration and enhancement is weighted as much or more than storm surge reduction and coastal community protection when it comes to spending oil spill fines.

Louisiana’s CPRA is trying to secure an approximate $280-plus million from various oil-spill penalty funds, including the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund as well as donations from nonprofit groups like Ducks Unlimited. Should the CPRA succeed, construction could begin in 2026 to restore more than 13 miles of beaches as well as sand dunes and pockets of back barrier marshes.

Here’s hoping CPRA succeeds. The Chandeleurs’ beaches and dunes are miniscule now compared to the estimated 11,000 acres there when Roosevelt established the refuge. Hurricanes, especially Georges in 1998 and, of course, Katrina in 2005 have ripped the islands apart, contributing to the loss of more than 90 percent of the landmass over the last 100 years.

Louisiana has lost far too much coastal habitat in the last century. That land loss has contributed to the slow erosion of a cultural identity intrinsic to the people of the Sportsman’s Paradise. Hopefully, restoring the Chandeleurs will play a big role in making sure that identity is passed on to the next generation of Louisiana sportsmen and women.

Every barrier island in Louisiana between the mouth of the Mississippi River and the Atchafalaya River has been restored and enhanced in some way in the last 25 years. It’s time the northern stretches of the Chandeleurs get their turn.

(Note: This story originally appeared in the October 2024 issue of Louisiana Sportsman.)

Banner aerial image credit: NOAA Restoration Center/ Erik Zobrist

TRCP gathered conservation leaders, recreational businesses, policy experts, and media at the 2024 OWAA Annual Conference to discuss the importance of a healthy Rio Grande

(El Paso, Texas) – The Thedore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership joined outdoor media and professionals at the Outdoor Writers Association of America’s annual conference in El Paso, Texas, to connect and learn from more than 150 outdoor storytellers – and the non-profits, brands, and communities that support their work.

As part of the conference, the TRCP hosted a panel discussion, moderated by Christian Fauser, the organization’s western water policy associate, to engage the outdoor writing community on the importance of a healthy Rio Grande in sustaining communities and outdoor recreation; what regional partners are doing to address river challenges; and how outdoor writers can help elevate the profile of this crucial watershed.

The Rio Grande/Rio Bravo is the third longest river in the continental US and is a source of life for more than 13 million people and countless unique wildlife species and ecosystems. The river also supports a vibrant outdoor recreational community and economy built around iconic landscapes such as Great Sand Dunes and Big Bend National Parks and a string of National Wildlife Refuges critical to sustaining migratory birds and other wildlife important to hunters, anglers, and wildlife watchers. The Rio Grande also faces tremendous challenges from a changing climate, dealing with the impacts of wildfires and drought, and declining water supplies.

Panelists included: Ashley Beyer, Southern Regional Director for US Senator Martin Heinrich; Martha Pskowski, El Paso-based energy and environment reporter for Inside Climate News; Toner Mitchell, Trout Unlimited New Mexico Water and Habitat Coordinator; and Mike Davidson, co-founder of Far Flung Adventures, and professional river guide.

The panelists provided crucial insights to the outdoor writers, non-profits organizations, businesses, and media on:

Learn more about TRCP’s commitment to habitat and clean water here

Photo credit: NPS Photo/Jennette Jurado

The TRCP is your resource for all things conservation. In our weekly Roosevelt Report, you’ll receive the latest news on emerging habitat threats, legislation and proposals on the move, public land access solutions we’re spearheading, and opportunities for hunters and anglers to take action. Sign up now.

If you’re a seasoned saltwater angler, you know that healthy estuaries mean healthy sportfish populations. Take the Chesapeake Bay or Florida Everglades, for example. Without these semi-enclosed, shallow-water systems and the menhaden, mullet, ballyhoo, herring, and other forage fish and crustaceans they support, there would be no recreational fishing because there would be no sportfish left that rely on them. What you might not know is that there’s a system of research reserves around the nation that for more than 50 years has been dedicated to conserving coastal habitat, while offering hunting and angling opportunities, youth education, and community support.

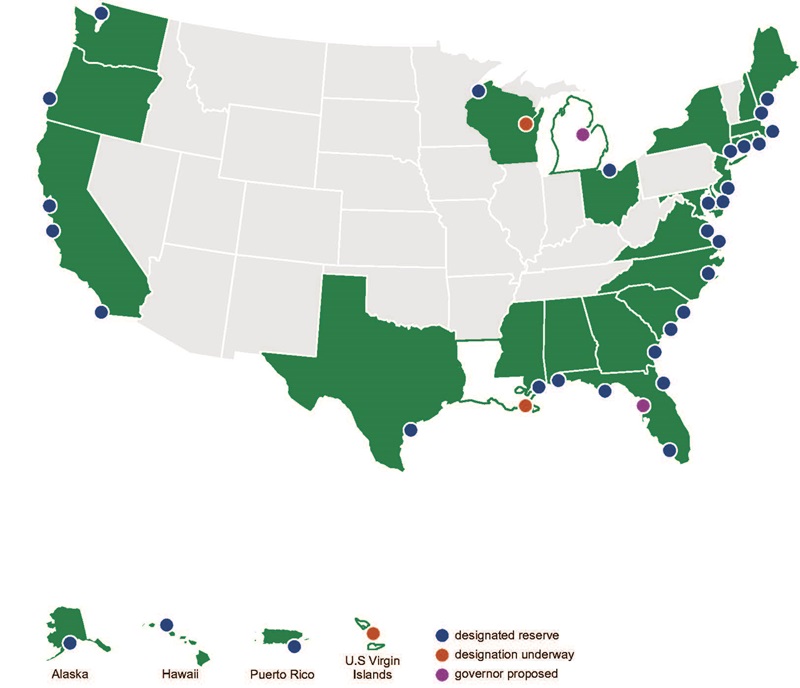

The National Estuarine Research Reserve System is a network of 30 coastal sites designated to protect and study the nation’s diverse estuarine systems, with sites on every coast and the Great Lakes. Funding is provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other federal agencies with matching state and private funds, and the reserves are managed by a state agency or university with input from local partners.

95 percent of the reserves allow fishing and 85 percent permit hunting.

The reserves span the breadth of the country’s highly varied estuarine habitats, such as mangrove forests, beaches, salt marshes, rocky intertidal zones, oyster reefs, and mud flats, and most contain extensive submerged aquatic vegetation that provides critical fish habitat. These reserves also provide public access to more than 1.4 million acres of coastal lands and waters.

“They protect places and people all around the coasts,” said Rebecca Roth, executive director of the National Estuarine Research Reserve Association (NERRA), a non-regulatory body that supports the system of reserves. “Every reserve is there because people cared passionately about the place and worked hard to get it designated.”

Over decades, National Estuarine Research Reserves have created a national dataset that provides a record of how coastal weather, water quality, sea levels, habitat, and vegetation have changed over time – all collected, synthesized, and analyzed according to stringent standards, to be used by scientists, resource managers, and others. Roth says the reserves also address climate change concerns at each site 365 days of the year, to track short-term changes and long-term trends on the coasts.

“We are the only national network that comes with a standardized estuary monitoring program, integrated science and education programs, strong connections to local communities, and a dedication to sharing what is learned across a national network,” Roth said.

Reserves provide key opportunities for education and training for outreach efforts about the data collected there. They demonstrate the value of conserving habitat to schoolkids and people of all ages, with more than 73,000 K-12 students benefiting in 2022 alone, and coordinate citizen science and volunteer cleanup efforts. Each year they sustain more than 10,000 jobs – providing significant local economic inputs – and are visited by more than 650,000 recreationists.

“Coastal reserves protect essential breeding habitats, act as natural buffers against rising sea levels, and support species adaptation to climate change,” said Jamelle Ellis, TRCP senior scientist. “By preserving ecosystems, they enhance climate resilience for wildlife and ensure sustainable outdoor recreation opportunities.”

The management plans that direct current reserves allow for recreational fishing in 28 of the 30 sites, and hunting in 25 of them. Regardless of whether sporting is allowed on these properties, however, all provide nurseries for species like sportfish and the forage fish they depend on for food. The wetlands and shellfish reefs they protect also help filter water and their lands serve as terrestrial habitat refuges for game species like deer and waterfowl to ensure more robust local populations. Other recreation activities popular at these sites include bird watching, hiking, and paddling.

NERRA’s Roth says that as more and more coastal lands are developed, the reserves become even more important as habitat for game species and places where anglers can target inshore species like redfish and striped bass. “We know that 75 percent of all fish caught begin their life in the nursery grounds of an estuary,” said Roth. “When you protect these waters and provide proper stewardship of the lands that surround them, you protect the nursery.”

In the late ‘60s, America’s coasts were under intense pressure from population growth and development was taking a toll on coastal lands, waters, and wildlife. As a result, in 1972 Congress passed the Coastal Zone Management Act to set national policy to “preserve, protect, develop, and where possible, to restore or enhance, the resources of the Nation’s coastal zone.” The act provided a backbone for creating the Research Reserve System. Through this act, states maintain rights to sustainably manage their own coasts while receiving federal financial and technical support. The act would later authorize the Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Program (CELCP), which protects ecologically important coastal lands and those with other values, such as recreational opportunities or historic features.

The CZMA has been amended 11 times since its initial passage to expand authorities and add focus areas, and NERRA is seeking in this federal legislative session for Congress to again reauthorize and update the reserve program and authorize funding for the Reserve System and the coast and estuarine land conservation program. Congress has not provided authorizations for either the national reserve system or CELCP since fiscal years 1999 and 2013, respectively.

“This has major implications for habitat protections, as the Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Program under the CZMA has already protected more than 100,000 acres using matched federal and state funding,” said David Pelikan, TRCP climate resilience program manager.

As it does every year, NERRA is requesting that Congress provide funding to address operations, research, facilities, and procurement and acquisition of new properties. Authorized funding amounts to reflect the needs of the coastal communities are being sought through passage of H.R. 6841, the Resilient Coasts and Estuaries Act, which was introduced in Congress last December. The bill would direct NOAA to designate five new reserves, significantly increasing the areas studied and protected and creating many more opportunities for angling and other public recreation, more habitat for fisheries, more coastal lands to protect communities from extreme weather, and more opportunities for businesses that rely on healthy coastal environments. The bill also would establish in statute existing reserve programs like Coastal Training that support fisheries, businesses, and communities and direct their execution as a matter of national policy, to ensure that these programs continue to serve communities in the future.

There are too many research reserves to allow detailed descriptions of each. Below are a few examples to demonstrate the breadth and variety of the system.

Rookery Bay

Located in southwest Florida near Naples, the Rookery Bay Research Reserve offers spectacular fishing, teeming with inshore fish species like redfish, snook, and tarpon in its extensive mangrove habitats, and provides refuge for more than 50 species of birds. It offers an environmental learning center, and as part of the Greater Everglades Ecosystem, its wetlands benefits from clean water coming south and serves as a final filter for water entering the Ten Thousand Islands area of the Greater Everglades Ecosystem. This reserve is closely tied into the local community and has used its offices to convene emergency responders during hurricanes. This is one of three reserves in Florida.

Click here to tell lawmakers to support Everglades conservation

Chesapeake Bay

With more than 30 miles of waterfront on the Maryland side of the Bay, the Chesapeake Bay Research Reserve offers extensive fishing access over oyster reefs and seagrass beds for inshore species like redfish and flounder – as well as edible invasive species like blue catfish – plus habitat for baitfish like menhaden, 44 miles of hiking/paddling trails, and a nature discovery center targeting youths. A similar reserve also exists on the Virginia portion of the Bay.

Kachemak Bay

Home to chinook and coho salmon, halibut, whales, and many seabirds, the Kachemak Bay Reserve’s research on juvenile salmon supports Alaska’s $595 million-dollar commercial fishing industry. Also, commercial fishermen are brought upstream of the reserve to learn firsthand about the importance of protecting the watershed’s habitat to benefit salmon and jobs that depend on them. The reserve brings $1.2 million of federal and state finding to the local economy each year and helps recreational shellfish harvesters respond to toxic algal blooms.

Any new reserves must permit existing recreational fishing and hunting.

Coming Soon

Designations are already underway for two new reserves in the U.S. – in Louisiana and Wisconsin. More will be added if Congress reauthorizes the CZMA. A third site in the U.S. Virgin Islands also would be advanced in its designation status, and a reserve in Michigan and new sites in Maine and Florida are in the pipeline. Any new reserve must permit existing commercial/recreational fishing, hunting, and other cultural uses.

A Louisiana reserve is already in the final review process for its designation. This site is located in the Atchafalaya Basin of the Mississippi River Delta and would support not only local fisheries and economies, but also protect coastal habitats, ensure a perpetual undeveloped buffer to protect communities from the more frequent and severe storms expected because of climate change, and create better access to the Atchafalaya Basin and its delta system of over 4,000 acres of wetlands. The reserve will also allow the opportunity to educate the public about sea level rise, land subsidence, and the importance of restoring more natural sediment flows from the Mississippi to build back land and wetland habitat.

Click here to learn how you can advocate for habitat-driven climate solutions in your state.

TRCP has partnered with Afuera Coffee Co. to further our commitment to conservation. $4 from each bag is donated to the TRCP, to help continue our efforts of safeguarding critical habitats, productive hunting grounds, and favorite fishing holes for future generations.

Learn More

Sign up below to help us guarantee all Americans quality places to hunt and fish. Become a TRCP member today.

Sign up to read our economic report on the jobs created by investing in conservation.