TRCP’s Nevada field representative Carl Erquiaga recently published the below story about hunting migrating mule deer with his granddaughters in the November 2024 issue of Fur Fish Game magazine. This long-established periodical will celebrate 100 years of contiguous publication in 2025

As I’ve grown older, having granddaughters has become one of the most enjoyable parts of my life. My eldest granddaughter Hayden, now 14, drew her first deer tag in our home state of Nevada in 2022. We did our best to make the most of the entire experience and it was, quite honestly, nothing short of perfect. She took a nice muley buck after hunting for several days, and the family was very proud of her – no one prouder than her Papaw.

Each child and grandchild my wife and I are blessed with has a special place in our hearts. My second granddaughter Carly, being my namesake, has a grip on me I cannot explain. She’s a little sassy with a wry sense of humor that we share. She’s also fiercely independent.

In 2023, Carly, age 12, became eligible for a hunting license. She hoped to draw one of Nevada’s coveted youth deer tags. Before she could buy a license and apply, she was required to pass the Nevada Department of Wildlife’s Hunter Safety course. I helped Carly study, went over gun safety as well as some basic wildlife management principles, and attended the class with her. She passed with flying colors.

When Hayden turned 12, I bought her first hunting license and helped her fill out the application for her tags. I did likewise for Carly. As luck would have it, Carly drew a northeast Nevada deer tag for the October 2023 season. The mule deer herd there is migratory, but I had confidence we’d find deer.

Carly prepared for the hunt all summer. She shot a .22 rimfire, then graduated to her uncle’s youth-sized .243 Winchester. True to family form, she was a natural shooter.

In mid-October, we – Carly, her father (my son-in-law) Garrett, and myself – packed my camp trailer and made the six-hour drive to the unit. We’d scheduled six days for the trip, but I didn’t believe we’d need that long. Oh, the best laid plans of mice and men.

As the sun illuminated the slope, we glassed the basin ahead and saw a group of does with three small bucks in the shadows.

We arrived at camp early enough to make a short afternoon hunt. As we made our way up the first of many rough, rocky roads, I asked Carly if she was ready to wake up at 4:30 a.m. every morning. “Yes!” she said, with no hesitation.

I told her I didn’t want to make this too much work, but hunting big game does require commitment. She said she was ready. I jokingly mentioned something about not wanting her to be grumpy in the morning.

“You know, Papaw, I’m generally a pretty jovial person,” she quipped. I tried to contain my laughter, recalling a slightly less than jovial stage – thanks to her fiercely independent streak.

We spent the evening glassing to no avail. It rained off and on most of the afternoon. With the temperature dropping, we returned to camp, ate and warmed up. The RV made it easy to keep Carly’s spirits high. We planned to be in another area at daylight.

I never sleep well the first night of a hunt, and when the alarm went off, it felt like I had just fallen sleep. I didn’t want to wake Carly, but to my surprise she popped out of bed and got her breakfast together, not quite jovial, but as good as one can be at 4:30 a.m.

We made it out of camp plenty early but had to wait for sunrise before going up the road. It’s a good thing we did. We hadn’t even reached the canyon when a young buck and doe crossed the road in front of us – no chance for a shot – so we eased up the trail to the ridge.

As the sun illuminated the slope, we glassed the basin ahead and saw a group of does with three small bucks in the shadows. They were a mile away, but we noted their location and turned up the ridge.

On top, Garrett spotted more does with one small buck in the draw below. They were working their way up the opposite ridge and soon disappeared over the top. We tried to cut them off, but rounding the last corner, into the draw, we saw does running, but no buck. I was about to whisper to Carly he might still be there, when he ran out, full tilt, stotted over the ridge, with no chance for a shot.

We spent the rest of the day glassing and checking new areas, ending up in the basin where the shadow bucks were at first light. We saw plenty of wildlife, including pronghorns, chukars, and sage grouse, but the bucks never materialized. Still, the day was a success because Carly remained in great spirits.

The next morning, we were up very early again, returning to where we’d been the first afternoon. It was October 14, when the solar eclipse passed over Nevada. We hoped to see it later that morning, if the clouds broke.

When we reached where we wanted to glass, a side-by-side UTV with three young men pinned behind binoculars greeted us. The canyon below showed three deer – two forkhorns and a small three-point – moving through brush toward the closest ridge. They were well out of range, so I took the opportunity to teach Carly some hunter etiquette. The other hunters were there first. I wanted to make sure we wouldn’t cut them off if we went after the bucks. I was ready to talk to them, but they picked up their gear, headed in a different direction, evidently not interested in the bucks.

Those bucks were exactly what we were looking for. As soon as the trio disappeared behind the ridge we went after them.

The memories made with my granddaughters were only possible with Nevada’s incredible wildlife. The deer we hunted migrate across hundreds of miles to their winter range. If we as hunters want to continue to make meaningful memories outdoors with our families, we must get involved in conservation efforts.

We made good time reaching where they’d fed, their tracks peppering the ground. We followed those tracks around to the edge of the canyon, when I spotted the bucks 140 yards on the opposite side, according to the rangefinder.

Feeding off each other’s excitement, I set up the tripod for Carly. One buck moved up the ridge between bushes where, if he stopped, Carly would have a good shot.

But he didn’t stop, traveling almost out of range.

I felt uncomfortable having Carly shoot at the moving buck. I felt it was better to let him go, and didn’t feel too bad when he ducked into some very thick aspens. The other two should be following shortly. One was that nice three-point.

We waited for his friends to come along. We waited and waited. But they never came out.

Now, I felt disappointed for not letting Carly try a shot. She might have connected when the buck wasn’t moving. I’d hoped for the better buck, but that wouldn’t matter to her. In fact, at one point, the little buck stepped out of the aspens, broadside, at 400 yards. She asked if she could try the shot. I told her no because she’d never shot that far. Better to be sure than take a risky shot.

Walking back to the truck, I was feeling bad. But Carly was still excited and looking forward to the eclipse. Kids are so resilient.

Watching the eclipse with her and her dad was a very special experience. The rest of that day and the next we continued to explore as much new country as we could. We saw deer every day, but no bucks within range or in places we could stalk. Some bucks we tried to stalk, only to find another hunter filled his tag on them. The others gave us the slip.

On Sunday night, the return trip looming, our spirits were low. We’d have time for a four-hour hunt that morning before breaking camp and heading home. At 4:30 a.m. we all moved a little slower, a little bit grumpy.

We went to the spot where Carly’s father had shot his first deer in 2020. That day, we only had time for a short hunt, but we made it happen. I hoped for a repeat. But despite checking several honey holes, we didn’t see a deer. Returning to camp, I told Carly I was sorry she didn’t tag a deer, and that I was proud of her great attitude and thanked her for wanting to hunt.

“It’s okay I didn’t get one,” she said. “But I am a little less jovial. There’s always next year. And I will be glad to get home, take a shower, and sleep in.”

Then she gave me a hug and said, “I love you, Papaw.”

I believe Carly learned a great deal about hunting and the responsibilities that go with it. I’m sure some of my ramblings about wildlife and its management challenges will sink in. And I know there are still good kids out there who are being given the tools to get through life and make good decisions. I’m very proud of my kids and grandkids.

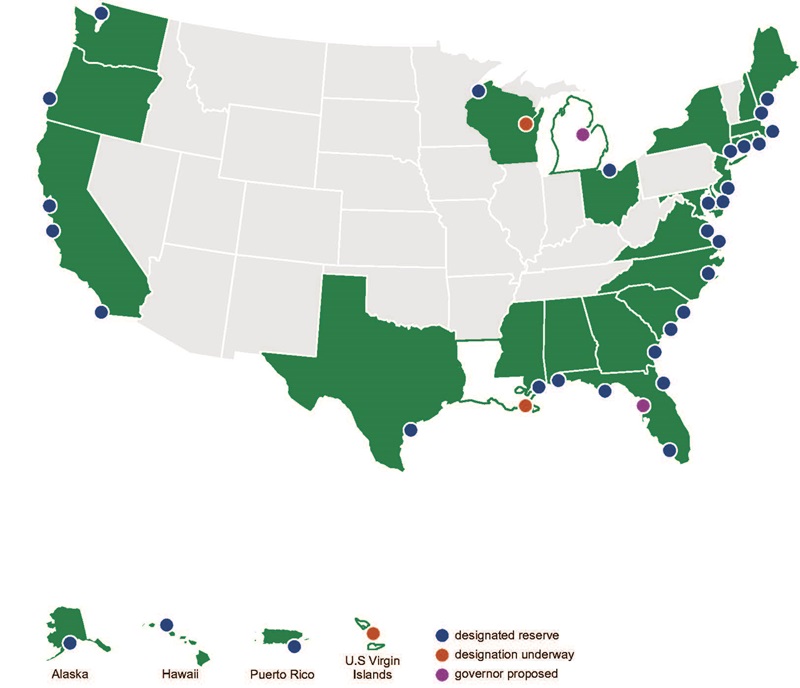

The memories made with my granddaughters were only possible with Nevada’s incredible wildlife. The deer we hunted migrate across hundreds of miles to their winter range. If we as hunters want to continue to make meaningful memories outdoors with our families, we must get involved in conservation efforts.

Subscribe to Fur Fish Game HERE.

Learn more about TRCP’s work on big game migration conservation HERE.

The TRCP is your resource for all things conservation. In our weekly Roosevelt Report, you’ll receive the latest news on emerging habitat threats, legislation and proposals on the move, public land access solutions we’re spearheading, and opportunities for hunters and anglers to take action. Sign up now.