Screen Shot 2020-08-04 at 10.59.27 AM

Do you have any thoughts on this post?

TRCP’s CEO attends White House signing ceremony

President Donald Trump today signed bipartisan legislation that invests in America’s public lands, waters, and outdoor economy.

Whit Fosburgh, president and CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, was among the conservation leaders who were invited to attend the historic signing of the Great American Outdoors Act.

“Hunters and anglers across the nation have a reason to celebrate today,” said Fosburgh. “The Great American Outdoors Act is the product of years of hard work by all segments of the outdoor community, from hunters and anglers to hikers and kayakers. To all the lawmakers who carried the water on Capitol Hill, we say thank you, and we thank President Trump for signing the bill into law. Today is proof that conservation stands above partisanship and political rancor.”

The Great American Outdoors Act fully funds the Land and Water Conservation Fund at $900 million annually, and invests $9.5 billion over the next five years to address the maintenance backlog on federal public lands.

Just like in the West, the history of how lands changed hands has contributed to today’s public access challenges

In the media and in popular imagination, public lands are most closely associated with Western snowcapped peaks managed by the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service or vast expanses of sagebrush prairie managed by the Bureau of Land Management.

But places like the Superior National Forest in Minnesota offer as much of a chance to immerse oneself in adventure as any of the public lands in the West. And for Midwestern hunters and anglers, there are millions of acres of state, county, and locally managed lands that provide critical access close to home.

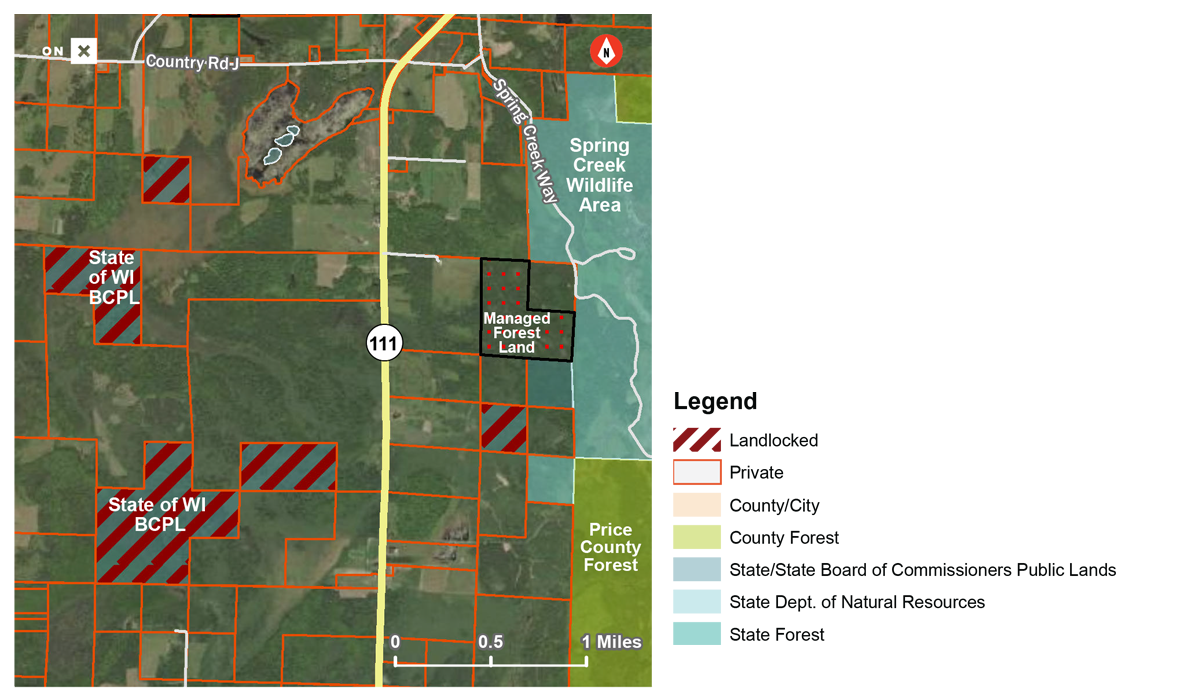

There are also as many as 300,000 acres of public lands in Minnesota and Wisconsin that are completely surrounded by private land, according to our latest report in partnership with onX. These lands represent lost hunting and fishing opportunities and a national challenge that is unfortunately becoming all too familiar—they’re your public lands, but you can’t get to them without asking someone’s permission.

As with other states in the West and Midwest, upon statehood the land base in Minnesota and Wisconsin was organized into six-by-six-mile squares known as townships according to the Public Land Survey System. Each township was further divided into 36 individual one-mile-square (640-acre) sections.

Both states received land grants from the federal government, originally comprised of two sections within each township, which were to be used to support public schools. Following statehood, several subsequent conveyances of federal land were provided to Minnesota and Wisconsin to serve various purposes, such as to support additional state institutions, create state parks and forests, expand agriculture, and retire marginal or unproductive farmland during the Great Depression. Meanwhile, millions of acres reverted back to counties and the states due in part to tax forfeiture.

Later, the Department of Natural Resources in each state began actively purchasing lands to meet management needs, generate revenue, protect critical fish and wildlife habitats, and provide access for sportsmen and women.

There were also vast federal public lands set aside in the Northwoods in the early 20th century, including the Chippewa and Superior National Forests in Minnesota and the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest in Wisconsin.

The result today is some of the most diverse public land holdings found anywhere in the nation and, unfortunately, a remnant patchwork of landlocked public lands.

Click here to read about three programs that offer solutions to the landlocked problem in the Midwest.

VISIT UNLOCKINGPUBLICLANDS.ORG

Top photo by Joe D via flickr.

These programs could serve as a model for other states with a growing tally of landlocked hunting and fishing areas

These days, thanks to GPS technology, anyone with a smartphone can take advantage of the hunting and fishing opportunities offered by even the smallest parcel of public lands. But what if you stumble across something like this, where there doesn’t seem to be any legal access to reach it?

You might think it’s a mistake, but there are actually more than 300,000 acres of these landlocked public lands in Minnesota and Wisconsin alone. Across the West, there are nearly 16 million landlocked acres.

Sure, you could knock on a few doors and request permission to cross private land into those crosshatched areas. But if access to public lands like these remains exclusive or temporary, we’re tying one hand behind our backs when it comes to recruiting and retaining the participation of new hunters and anglers.

For a Midwestern hunter looking to hang a treestand for whitetails, set up an ambush for turkeys, or work a woodlot for grouse—especially for the first time—a small or overlooked public parcel could be a game-changer. And easy access to a lake shore or riverbank might give a parent the only place they’re be able to teach their kids to fish for walleye, pike, or smallmouth bass.

Strategically unlocking as little as a few dozen inaccessible acres at a time could mean the difference between a young person having a place to hunt or not. A lifelong passion for fishing—and the conservation funding raised by those license purchases—could hang in the balance.

Landlocked public lands are best made accessible through cooperative agreements with private landowners that result in land exchanges, acquisitions, and easements, but this critical work cannot be facilitated by land trusts, conservation organizations, and public agencies without funding.

When thinking about opening inaccessible public lands, even small projects can offer big benefits. Here are three programs that support these efforts.

The federal LWCF remains the most powerful tool available for establishing and expanding access to public lands and waters. And it just got more powerful, with the recent passage of the Great American Outdoors Act, a bill that fully funds the program at $900 million annually in support of wildlife conservation and outdoor recreation, including $27 million that is dedicated to public access. Importantly, the LWCF is not just limited to federal projects—at least 40 percent of the program must be used for state-driven projects, making it available to help open state- and county-owned lands for public recreation.

Established by the voters of Minnesota in 2008, the Outdoor Heritage Fund is supported through the state sales tax. This program empowers projects that protect, enhance, or restore prairies, wetlands, forests, or other habitat, and—when it meets those primary goals—can also be used to open or expand access to inaccessible wildlife management areas managed by Minnesota DNR’s Fish and Wildlife Division. With an estimated $100 million available in 2022, the Outdoor Heritage Fund is a heavy hitter in support of conservation and access.

Created in 1989, this program exists to preserve valuable natural areas and wildlife habitat, protect water quality and fisheries, and expand opportunities for outdoor recreation. With a budget of $33 million in 2019, Knowles Nelson is a major program that, among other things, can help unlock Wisconsin’s state parks, wildlife and fisheries areas and state natural areas. Knowles Nelson is set to expire in 2022 and will need to be renewed by the state legislature. State decision makers need to know the importance of this program for wildlife habitat and public access.

Both Minnesota and Wisconsin have innovative state programs for conserving habitat and improving access that should serve as valuable models for other states looking to do the same. Support local ballot initiatives and state legislation to set aside these dedicated funds where you live.

To dig into the data we’ve uncovered on inaccessible public lands across the country, click here.

Backcountry Conservation Areas near Missoula and Lewistown will safeguard recreational opportunities and wildlife habitat

(Missoula, Mont.)–The Bureau of Land Management today announced it’s finalizing new Resource Management Plans in western and central Montana that will shape hunting and fishing opportunities for generations to come.

These two plans will guide the future of forest and grassland management, wildlife habitat, fisheries conservation, and outdoor recreation on approximately 900,000 acres of public lands east of Missoula, surrounding Lewistown, and in and around the Missouri River Breaks. In response to requests from sportsmen and women, the final plans include Backcountry Conservation Areas, a new multiple-use framework aimed at conserving prized big game habitat and hunting and fishing areas.

“Thanks to these plans sportsmen and women will experience high-quality big game hunting in places like the Hoodoos and Ram Mountain in the Missoula area, as well as Arrow and Crooked Creeks in central Montana,” said Scott Laird, Montana Field Representative with the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. “We appreciate that the Montana BLM listened to the input of many hunters and anglers and adopted Backcountry Conservation Areas in the final plans.”

The Missoula Field Office plan guides the management of local landmarks including the Blackfoot River corridor and portions of the Garnet and John Long mountain ranges. The revision process was formally initiated in early 2016 with a scoping phase and then the draft plan was published in May 2019. Hunters, anglers, the state of Montana, tribal representatives, Missoula County, and other entities spoke up in support of Backcountry Conservation Areas in the highest value wildlife and recreation areas. Those comments are reflected in the final plan.

In the Lewistown Field Office, which encompasses some of Montana’s best elk hunting units in the Missouri River Breaks, the planning revision process unfolded along a parallel timeline to Missoula’s. Similarly, strong support from the sporting community, the state of Montana, and local conservation groups led BLM decision-makers to include Backcountry Conservation Areas in the Crooked Creek and Arrow Creek areas.

“While the Lewistown RMP didn’t include everything we asked for, we are grateful that our comments generated some compromise, said Doug Krings, the Region 4 Chapter Leader for Backcountry Hunters & Anglers. “In particular, the addition of the BLM’s new Backcountry Conservation Areas—which ensure that wildlife and wild places will stay intact and productive for hunters and other outdoor recreationists—is something that all public land owners are pleased to see.”

“The recently released plans are not perfect, but Trout Unlimited appreciates changes in the final Lewistown plan that give greater consideration for the conservation and restoration of rare native trout populations in the Judith Mountains,” said Colin Cooney, Montana field coordinator for Trout Unlimited. “We also feel that this RMP sets a new, much-welcomed standard for stream buffers in the West and one that we are going to work with other field offices to adopt in a region where economic diversity is so important. Specifically, the plan includes ½ mile oil and gas development buffers for all Blue and Red Ribbon fisheries, native trout streams, and streams suitable for restoring populations of Westslope cutthroat trout. We thank the BLM for including this necessary, balanced, and common-sense bar of protection for our most important trout fisheries.”

In collaboration with landowners, local government officials, and other stakeholder groups, several hunting and fishing organizations helped activate sportsmen and women to provide meaningful feedback on the draft plans that was then incorporated into the final proposals.

Photo: Charlie Bulla

From now until January 1, 2025, every donation you make will be matched by a TRCP Board member up to $500,000 to sustain TRCP’s work that promotes wildlife habitat, our sporting traditions, and hunter & angler access. Together, dollar for dollar, stride for stride, we can all step into the arena of conservation.

Learn More